PERU / MACHU PICCHU

June 26—July 11, 2001

THE BIG PICTURE

Getting

to and from Peru takes a while. Getting around while in Peru also takes

a while.

We

flew from Denver at about 4:00 p.m. to Miami and then overnight

to Lima

(The airport is in Callao, about 10 miles to the west on the Pacific). From Lima we flew

an hour to Cusco in

the highlands at about 11,000' and  finally the last leg of 45 minutes

to Puerto

Maldonado, a town of about 30,000 situated on the Rio Madre de Dios

near the borders of Brasil and Bolivia. After three days at

the Lake Sandoval Lodge in the Amazon rain forest,

we returned to Cusco where we explored the city (of about 250,000) and

the Sacred

Valley for four days. A train took us up the Urubamba River to Kilometer

88 where we began our four day hike on

the Inca

Trail (called the most popular hike in the world)

to Machu

Picchu, the most visited attraction in South America. After two days

at the Inca city, we returned to Cusco by train and bus for a day of R

& R. On our final day we flew to Lima for a city tour and farewell

dinner before boarding the plane for Dallas–Ft. Worth and on to Denver.

finally the last leg of 45 minutes

to Puerto

Maldonado, a town of about 30,000 situated on the Rio Madre de Dios

near the borders of Brasil and Bolivia. After three days at

the Lake Sandoval Lodge in the Amazon rain forest,

we returned to Cusco where we explored the city (of about 250,000) and

the Sacred

Valley for four days. A train took us up the Urubamba River to Kilometer

88 where we began our four day hike on

the Inca

Trail (called the most popular hike in the world)

to Machu

Picchu, the most visited attraction in South America. After two days

at the Inca city, we returned to Cusco by train and bus for a day of R

& R. On our final day we flew to Lima for a city tour and farewell

dinner before boarding the plane for Dallas–Ft. Worth and on to Denver.

GREAT TRIP #5

Judy and I have been fortunate

to have traveled a good bit during our 40 years of marriage: most of the

US (we have missed North Dakota); Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean; parts of Europe;

Australia and New Zealand. Looking back, we have enjoyed what truly have

been, for us, four Great Trips: the UK and Ireland (1982), rafting the

Grand Canyon (1995), Mexico’s Copper

Canyon (1998), and Australia

/ New Zealand

/ Fiji

(1999). Our two weeks in Peru, particularly hiking the Inca

Trail and discovering for ourselves Machu Picchu, has been an experience

that we consider Great Trip #5.

“In

the variety of its charms and the power of its spell, I know of no place

in the world which can compare with it. Not only has it great snow peaks

looming above the clouds more than two miles overhead, gigantic precipices

of many–colored granite rising sheer for thousands of feet above the foaming,

glistening, roaring rapids; it has also, in striking contrast, orchids

and tree ferns, the delectable beauty of luxurious vegetation, and the

mysterious witchery of the jungle.” (Hiram Bingham)

Machu

Picchu is a destination that Judy has talked about for years. Our first

thought was to sign on with Elderhostel which makes several trips there

each year. Two years before, we attended a slide show on Machu Picchu presented

by Cindy Sonderup, the owner of Changes in

Latitude, a travel store in Boulder. She had made the trip several

times and her slides were  excellent. More important to us, the trip she described involved hiking the Inca Trail

in order to enter Machu Picchu. She explained that, in addition to all

we would experience along the hike, the benefit of this was the opportunity

to spend more time at the site, especially in the evening and at sunrise

when there were not the crowds who were bused in each morning and who were

bused out mid–afternoon. We would, of course, have to camp, sleep on the

ground, carry a day pack, have the benefit of guides and porters (to carry

the tents, equipment, propane tanks, etc.). It seemed like exactly what

we were looking for in a trip: new places, exercise, and a group leader

like Cindy, who was organized and great fun to be with. While we couldn’t

go in 2000, we put ourselves on the list for 2001.

excellent. More important to us, the trip she described involved hiking the Inca Trail

in order to enter Machu Picchu. She explained that, in addition to all

we would experience along the hike, the benefit of this was the opportunity

to spend more time at the site, especially in the evening and at sunrise

when there were not the crowds who were bused in each morning and who were

bused out mid–afternoon. We would, of course, have to camp, sleep on the

ground, carry a day pack, have the benefit of guides and porters (to carry

the tents, equipment, propane tanks, etc.). It seemed like exactly what

we were looking for in a trip: new places, exercise, and a group leader

like Cindy, who was organized and great fun to be with. While we couldn’t

go in 2000, we put ourselves on the list for 2001.

Additional

benefits of the trip with Changes in Latitude were the small size of the

group (13 plus Cindy), the range of ages (12–65), and all from Colorado,

most from Boulder County (which turned out to be a plus). Cindy’s selection

of local guides was perfect and, because she went with us, we knew she

would do everything possible to see that we had a great time doing all

the things that had made the trip a good one for her. And she did. We had

a terrific time. Group size and compatibility among trip members are essentials,

but the key is a group leader who understands why people travel and how

to get the most out of a trip. Cindy is first rate!

SOME (FAIRLY) BRIEF HISTORICAL FOOTNOTES

The

history and culture of the group known today as “the Incas” is derived

from myth, new agers,

Spanish historians, oral traditions, and a variety of artifacts the most

remarkable of which are the ruins of cities, roads, buildings, and other

signs that their empire was wealthy and far–reaching. At its height, the

Incas claimed dominion over a strip of land along the west coast of South

America that extended from Colombia over 2,400 miles to southern Chile

and Argentina, far larger than the empires of Alexander or the Aztecs.

Though there were several important cities, the Inca capital was Cusco

(Qosco), Quechua for

“the navel,” the center of the Inca Empire.

The

ancestors of the Incas migrated into the Sacred Valley in the thirteenth

century under legendary Manco Capac and established the city of Cusco.

They consolidated their hold over the region for nearly two hundred years.

It was the fifth of these rulers (there were 13 in all), Inca Roca, who

initially took the title “Inca,” or “emperor.”

The

domain of the Incas remained small until, in the 15th century, Yupanqui,

a son of the Inca Viracocha, and a small cohort of warriors routed an attempted

invasion by an army of Chancas. Although his father still lived and favored

another son for the succession, the people acclaimed the bold young prince

as their new ruler who took the name “Pachacuti.” Beginning in 1438, Pachacuti

resolved to rebuild Cusco as a lasting monument to Inca glory and a ceremonial

center. As he expanded his empire outward from Cusco, he built an immense

stone fortress called Sacsahuaman on the heights above the city. By the

time of his death, Pachacuti and his kin had expanded the empire in all

directions, earning it the Quechua name “Tahuantinsuyu,” the Four Quarters

of the World. His son, Tupa Inca Yupanqui (“the Unforgettable One”) continued

the expansion, more than doubling the size of the empire (approximately

1471–1493). His successor, Huayna Capac,

expanded

the empire to its greatest extent.

In

1525, Inca Huayna Capac died of smallpox, a disease brought by the Spanish

invaders to the New World. Although the Spanish had explored only the northern

fringes of Inca territory at this time, the disease they had brought with

them was already spreading, decimating the Indian population. The efficient

Inca communication system proved to be Huayna Capac’s undoing: the chasqui

(messenger) who brought the Inca news of the appearance of the white men

and their new disease also brought the virus itself.

Huayna

Capac had designated his son Huascar as his heir. When Huascar was invested

as Inca in Cusco, his brother Atahuallpa had stayed behind in the northern

capital of Quito, sending gifts south to Huascar. The newly invested Inca,

however, cut off the noses of his brother’s ambassadors, making it clear

to Atahuallpa that any loyalty to his brother would be similarly rewarded.

Years of bloody warfare between the brothers eventually ensued. Eventually,

Atahuallpa’s army set a trap for Huascar, captured him, sacked Cusco, and

executed Huascar.

Rumors of rich kingdoms and

gilded rulers began to reach the Spaniards soon after they reached the

New World. Cortez’s conquest of Mexico in 1519 raised the level of greed

and excitement to fever pitch, inspiring numerous other expeditions to

various parts of the New World. Between 1522–1533, starting in the north,

Francisco

Pizzaro made three expeditions of exploration and conquest motivated,

like all Spaniards coming to the new world, by the Three Gs: Gold, God,

and Glory. His tiny army of fewer than 150 men subdued an empire of an

estimated 10,000,000 people through stealth, dishonesty, infectious diseases,

Inca naiveté and internal political turmoil—and guns! It took Pizzaro

nearly 40 years to eradicate the empire, but in 1572, the last Inca, Thupaq

Amaru who led an unsuccessful rebellion against the Spanish, was executed

in the main square in Cusco, bringing to a final end one of the most powerful

and influencial—and amazing—groups of people to have lived.

Today, when Incas are mentioned,

the first image is that of Machu Picchu, the city built in just 30 years

and abandoned before the Spanish conquest and presumably never explored

until 1911 when Yale/Harvard scholar

Hiram Bingham was shown the long–rumored

“Lost

City” by a local Quechua:

“The

morning of July 24th dawned in a cold drizzle. Arteaga (a local farmer)

shivered and seemed inclined to stay in his hut. I offered to pay him well

if he showed me the ruins. He demurred and said it was too hard a climb

for such a wet day. But when he found I was willing to pay him a sol, three

or four times the ordinary daily wage, he finally agreed to go. When asked

just where the ruins were, he pointed straight up to the top of the mountain.

No one supposed that they would be particularly interesting. And no one

cared to go with me.”

Accompanied

only by Seargeant Carrasco (Bingham’s interpreter) and Arteaga, Bingham

left the camp around 10 am. After a short while the party crossed a bridge

so unnerving that the intrepid explorer was reduced to crawling across

it on his hands and knees. From the river they climbed a precipitous slope

until they reached the ridge at around midday.

Here

Bingham rested at a small hut where they enjoyed the hospitality of a group

of campesinos. They told him that they had been living there for about

four years and explained that they had found an extensive system of terraces

on whose fertile soil they had decided to grow their crops. Bingham was

then told that the ruins he sought were close by and he was given a

guide, the 11 year old Pablito Alvarez, to lead him there.

Bingham

announced his “discovery” in articles and photographs published for the

National Geographic Society and other publications, returned at least one

other time to excavate and clean the vegetation from the principle areas,

and later went into politics and business. He died in 1956.

THE RAINFOREST / LAKE SANDOVAL

LODGE

When

our plane touched down in Puerto Maldonado, we hesitated to leave the plane,

expecting the worst humidity and heat and bugs. We were, after all,

deep in the heart of the southern region of the

great Amazon basin. Puerto Maldonado sits isolated on the banks of the muddy Rio

Madre de Dios which, like hundreds of other rivers on the east slope of the Andes,

eventually makes its way to the great Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean.

deep in the heart of the southern region of the

great Amazon basin. Puerto Maldonado sits isolated on the banks of the muddy Rio

Madre de Dios which, like hundreds of other rivers on the east slope of the Andes,

eventually makes its way to the great Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean.

To our relief

and delight, the temperature was in the 70s, the humidity light (at most

40%), and not a bug in sight. Of course it was winter in Peru, but more

important, we landed in the middle of a “cold spell” that would last for

the three days of our stay.

We

were bused from the airport to the river, boarded a long, narrow “canoe”

with a 55–hp outboard motor, traveled about 45 minutes out of town to a

“landing” where we climbed the dirt bank to the top, hiked about two miles

into the jungle to a spot where a channel had been cut connecting the trail

through a swamp with Lake Sandoval.

Small canoes took us through the swamp and a mile or so across the lake

to a real dock where we climbed the stairs to the lodge and our rooms.

Much like other jungle lodges, the accommodations were clean, comfortable

and no–frill rooms with a private bath and hot water on demand; screens

everywhere (including the ceiling which was open to the other 15 or so

rooms in our wing); and electricity generated from 6–10 am, 12–1 pm, and

6–10 pm. Our beds were covered all around with mosquito netting, but we

didn’t really need them during our time there.

Meals were served in the lodge’s

main building that adjoined the two wings of rooms. Food was local and delicious

(e.g., our first meal, lunch, featured chicken and rice wrapped and steamed in

banana leaves in addition to soup and dessert).

We met our local guide, Javier, at

lunch and spent the afternoon quietly boating on the lake in search of birds (vultures, egrets,

anhingas,

orapendula,

herons, parrots, macaws, kingfishers, nighthawks, among others),

caimans

(saw only their eyes and then just as red dots at night when the flashlights

struck them), monkeys (howlers, capuchins, squirrels),

giant otters, turtles, and bats.

(vultures, egrets,

anhingas,

orapendula,

herons, parrots, macaws, kingfishers, nighthawks, among others),

caimans

(saw only their eyes and then just as red dots at night when the flashlights

struck them), monkeys (howlers, capuchins, squirrels),

giant otters, turtles, and bats.

Our

routine was to get up at 5:00 am for canoeing around the lake, breakfast,

a hike along one of the trails on the grounds of the lodge for either tree

and animal identification or to learn about medicinal plants. After lunch

was generally free time due to the anticipated heat of the day (though

we usually went out in the canoe on our own). A late afternoon/early evening

group canoe ride around the lake was followed by one of the best times

of the day: a shower followed drinks together in the main lodge (usually

wine or cold beer, but no

pisco

sours since there was no ice available) and a late dinner.

One

variation in our routine was an early morning canoe ride and hike at dawn

to a spot in the jungle Javier knew about where macaws by the hundreds

gather each morning. It was loud and busy with birds getting in each

others’ faces, competing for a particular branch or place on a limb. At

about 7:15, they all get some unseen signal and fly off in family groups

to feed all day.

Lake

Sandoval was an excellent place for photography: animals, trees, different

light conditions and water to reflect everything back on itself. There

is a quietness about the place, a peacefulness that I think we all appreciated

after airport, traffic, airplanes, etc. By our last day, the temperature

began to climb to its normal warmth so that two ice cold beers before lunch

did not seem out of place.

Our experience here was very reminiscent

of our visit to Selva

Verde Lodge in Costa Rica: the setting was identical in many ways—comfortably

rustic, lush vegetation, and lots of exotic plants and birds (plus lots

of butterflies at Selva Verde). Both were very much like Belize, Australia,

and areas we’ve visited in Mexico leading us to suspect that rain forests,

perhaps everywhere, have lots in common.

Beginning

our 16–day trip in this location was a good idea. We’d spent nearly 16

hours on planes, buses, and canoes, and we all needed to slowly stretch

our muscles, not have to deal with big city stress or high altitude (that

would come later), and get to know each other in a relaxing atmosphere.

The group of 14 is very congenial, comfortable, considerate, and uncomplaining.

We would get along famously for the next two weeks!

CUSCO AND THE SACRED VALLEY

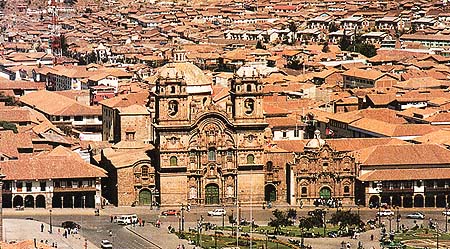

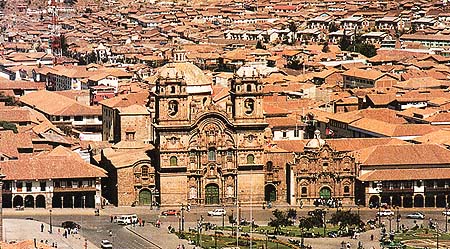

There are reminders of the Incas throughout the city of Cusco. When the

Spanish arrived in 1533 it was a city as modern as most any in the world; within

a few brief years, churches were built from (and on) Inca walls and temples

in a concentrated effort to destroy the old gods and create a Spanish colonial

town on the ruins of the Inca capital. The cathedral of Cusco (shown on the left and below)

faces the Plaza de Armas in the center of the city. In 1983 it was, along with Machu Picchu,

the first of ten locations in Peru to be declared

a World

Heritage Site. During our few days there, we visited both Inca and

Spanish sites aware that both traditions are very much alive.

There are reminders of the Incas throughout the city of Cusco. When the

Spanish arrived in 1533 it was a city as modern as most any in the world; within

a few brief years, churches were built from (and on) Inca walls and temples

in a concentrated effort to destroy the old gods and create a Spanish colonial

town on the ruins of the Inca capital. The cathedral of Cusco (shown on the left and below)

faces the Plaza de Armas in the center of the city. In 1983 it was, along with Machu Picchu,

the first of ten locations in Peru to be declared

a World

Heritage Site. During our few days there, we visited both Inca and

Spanish sites aware that both traditions are very much alive.

Just

a half block from the small Plaza Cusipata is El

Hotel Picoaga, originally the opulent residence of the Marquis de Picoaga

and later converted into a comfortable four star hotel that surrounds an

inner courtyard. The location gave us great access to the central Plaza

de Armes, the Cathedral, shopping, and not a few street vendors who camped

out on the sidewalk just outside the hotel entrance.

Our first afternoon was spent on a

city tour,  primarily

several of the 40+ churches that serve the residents of Cusco, including

Santo Domingo with its Spanish wall built upon the huge Inca stones so

carefully carved, notched, and set smoothly upon each other; San Blas with

its ornate wood pulpit so intricately carved; and the cathedral which is

undergoing extensive renovation, a project of several years and many millions

of soles (financed in large part by the Peruvian telephone company which,

we were assured, accounted for why the telephone rates were so high). We

had hoped to see, in addition to the gold and silver altar pieces and fine

sculptures, the Spanish–Inca rendition of the Last Supper painted in part

by a traditional Spanish master, and in part by local Quechua painters

who painted in a local delicacy, cuy

or guinea pig, as the main course! Unfortunately, the area of the painting

was off limits to visitors.

primarily

several of the 40+ churches that serve the residents of Cusco, including

Santo Domingo with its Spanish wall built upon the huge Inca stones so

carefully carved, notched, and set smoothly upon each other; San Blas with

its ornate wood pulpit so intricately carved; and the cathedral which is

undergoing extensive renovation, a project of several years and many millions

of soles (financed in large part by the Peruvian telephone company which,

we were assured, accounted for why the telephone rates were so high). We

had hoped to see, in addition to the gold and silver altar pieces and fine

sculptures, the Spanish–Inca rendition of the Last Supper painted in part

by a traditional Spanish master, and in part by local Quechua painters

who painted in a local delicacy, cuy

or guinea pig, as the main course! Unfortunately, the area of the painting

was off limits to visitors.

The next two days were spent outside Cusco visiting important Inca

sites with our guide, Fredy Delgado, who would be with us the rest of the trip. On

Sunday, July 1, we headed to Ollantaytambo, a fortress–city on the Urubamba

River about 45 miles northwest of Cusco. On the way, we passed the Sunday

market in the small town of Chinchero.

We smelled bargains and saw photos that needed to be taken, so we stopped

for an hour or so. We continued over the mountains to Urubamba and on to

Ollantaytambo. The origin of the place name is likely fiction, but it makes

a wonderfully romantic tale nonetheless and is worth repeating:

The next two days were spent outside Cusco visiting important Inca

sites with our guide, Fredy Delgado, who would be with us the rest of the trip. On

Sunday, July 1, we headed to Ollantaytambo, a fortress–city on the Urubamba

River about 45 miles northwest of Cusco. On the way, we passed the Sunday

market in the small town of Chinchero.

We smelled bargains and saw photos that needed to be taken, so we stopped

for an hour or so. We continued over the mountains to Urubamba and on to

Ollantaytambo. The origin of the place name is likely fiction, but it makes

a wonderfully romantic tale nonetheless and is worth repeating:

Ollantay

was an officer in the army of Inca Pachacuti who rebelled against Pachacuti

because he was in love with Pachacuti’s daughter and was denied her hand

in marriage. He took refuge in the town of Tampu (meaning shelter

or stopping place) and declared himself the new Inca. The “rebellion” was

quickly crushed, Ollantay was sent to prison, but not before Pachacuti’s

daughter bore a child named Ima Sumaq (also the name taken by a remarkable

Peruvian singer: Yma Sumac).

When Pachacuti died, the next Inca, Tupa Inca Yupanqui, pardoned Ollantay

and allowed the marriage. The town became known thereafter as Ollantaytambo

and the statue of Ollantay stands in the center of town.

We visited a modest home in town with guinea

pigs skittering about the floor (future dinners, perhaps?), skulls of family

members on a cornice shelf, and an ekeko

(the figure in red on the right) for good luck. From town we climbed the

terraces and walls of what the Spanish called “The Fortress” that was an

easily defended position built out of huge porphyry monoliths, some over

12 feet high and weighing many tons. They were quarried over six miles

away on the other side of the Urubamba River.

pigs skittering about the floor (future dinners, perhaps?), skulls of family

members on a cornice shelf, and an ekeko

(the figure in red on the right) for good luck. From town we climbed the

terraces and walls of what the Spanish called “The Fortress” that was an

easily defended position built out of huge porphyry monoliths, some over

12 feet high and weighing many tons. They were quarried over six miles

away on the other side of the Urubamba River.

Our

next stop, after a late lunch, was the picturesque market town of Pisac

(P’isaq). The Inca town of Pisac lies in ruins on the hillsides above the

town; today’s Pisac was created by the Spanish to contain the conquered

Quechua in one place in order to indoctrinate them into the Spanish religion

and to control them as laborers for the Spanish settlements. The name Pisac

means “reduction of Indians,” something the Spanish came prepared to do.

The famous Pisac market is a Sunday event, though the shops/stalls appear

more permanently constructed like an on–going flea market. While it was

fun to poke through the endless supply of sweaters, clay figurines, rugs,

etc., it was late in the day, rain threatened, and the vendors seemed tired

and listless. The morning stop at the outdoor market at Chinchero was much

more lively and almost festive.

Though

we were only 18 miles from Cusco, the trip at dusk over the mountains seemed

five times longer. We returned tired, some of us suffering from slight

stomach upset and hastened to our rooms for a rest and some Cipro or Immodium.

A good night’s sleep helped.

The next day we traveled

by bus a short ways out of town to the ruins of

Saqsaywaman

(or “sexy woman,”  as

the local guides suggest in a smarmy helpful way). The enormous walls are

comprised of massive granite monoliths that measure up to 16 feet high

and wide and weight up to 130 tons; it is a testimony to the engineering

genius of the Incas that they were able to cut, move, and place these stones

with the kind of precision that remains. There are a number of theories

regarding the purpose of the site: was it a castle? a fortress? a fortified

temple and city? or a complex suburb of Cusco? Whatever it was, what remains

staggers the imagination to explain how it came to be constructed. Walking

among the remaining walls is to walk as an ant in a boulder field. Along

with the massive ruins at Ollantaytambo, Saqsaywaman gave us a glimpse

of what we were to find at Machu Picchu and along the four day hike on

the Inca Trail.

as

the local guides suggest in a smarmy helpful way). The enormous walls are

comprised of massive granite monoliths that measure up to 16 feet high

and wide and weight up to 130 tons; it is a testimony to the engineering

genius of the Incas that they were able to cut, move, and place these stones

with the kind of precision that remains. There are a number of theories

regarding the purpose of the site: was it a castle? a fortress? a fortified

temple and city? or a complex suburb of Cusco? Whatever it was, what remains

staggers the imagination to explain how it came to be constructed. Walking

among the remaining walls is to walk as an ant in a boulder field. Along

with the massive ruins at Ollantaytambo, Saqsaywaman gave us a glimpse

of what we were to find at Machu Picchu and along the four day hike on

the Inca Trail.

INCA TRAIL AND MACHU PICCHU

Finally we began the journey

that had brought us to Peru. The Amazon jungle gave us a chance to relax

from the flight and get to know each other in a new setting. The four days

in Cusco gave us some altitude experience and a preview of the Inca Empire

crown jewel, Machu Picchu. Getting there was as important to us as our

arrival.

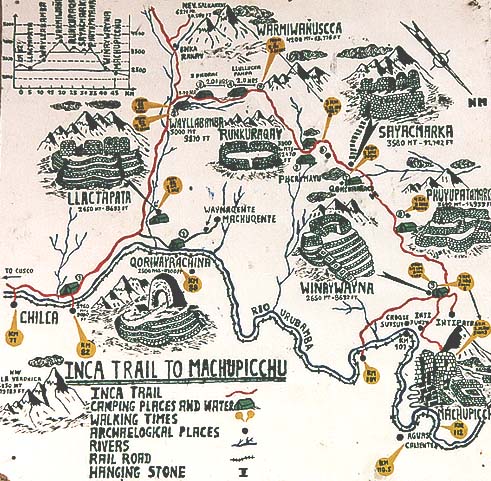

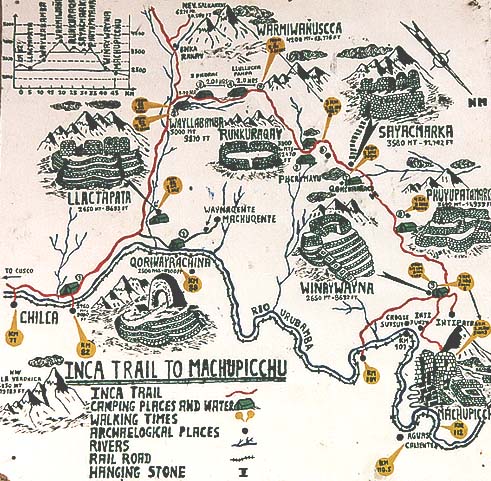

We began by boarding a 7:30

train in Cusco. We cleared the city after six switch backs, passed through

fertile farming areas, caught glimpses of Mount Veronica (nearly 19,000'),

passed by Ollantaytambo at Km 68, and finally arrived at Km 88, a nondescript

siding where we got off, collected our belongings, signed in at the official

registration point, crossed a footbridge over the Rio Urubamba, and walked

less than a mile to our first campsite at Qente, near the ruins of Llaqtapata,

an agricultural city with terraces for growing, temples, residences, and

a wall paralleling the Kusichaka River. We enjoyed a hearty lunch and a

five mile warm–up hike through a eucalyptus grove and onto the main trail

we would go back over again in the morning. Before dinner some rested in

their tents while a few fierce competitors in our group joined the guides

and some local flat bellied twentysomethings in several tough games of

soccer until dark.

Our first full day on the

Inca Trail was the equivalent of hiking to the top of Longs Peak (about

4000' elevation gain in just over seven miles). The day was generally cloudy

and we would climb continually before reaching camp at Llulluchapampa just below

Warmiwanusqua  (Dead

Woman Pass) the highest pass on the Trail at 13,780'. We stopped for a

short rest at Willkaraqay, a pre–Spanish village—the last place to buy

anything, we thought—and pushed ever upwards along the wide stone trail.

A couple of our group completed the 2–3 mile leg of the trip by horseback!

The air was thin, and the views of the snow–capped peaks were breathtaking.

We stopped for lunch about 11:15 at a table set up before our arrival by

the cooks and a few porters (the rest had gone on to set up camp at Llulluchapampa)

overlooking the valley from which we had just climbed. Another hour of

ascent through a lush cloud forest and we arrived at camp, a bit tired

but exhilarated by the view at 12,000'. Judy was first in; Hughes was in

the back of the pack as usual. We rested in our tents for a couple of hours

(we really should have brought a book) until “tea” at about 3:30. Fredy

was somehow able to get (in the middle of nowhere!) a six pack of cokes

which some found more to our liking than instant coffee or teas.

(Dead

Woman Pass) the highest pass on the Trail at 13,780'. We stopped for a

short rest at Willkaraqay, a pre–Spanish village—the last place to buy

anything, we thought—and pushed ever upwards along the wide stone trail.

A couple of our group completed the 2–3 mile leg of the trip by horseback!

The air was thin, and the views of the snow–capped peaks were breathtaking.

We stopped for lunch about 11:15 at a table set up before our arrival by

the cooks and a few porters (the rest had gone on to set up camp at Llulluchapampa)

overlooking the valley from which we had just climbed. Another hour of

ascent through a lush cloud forest and we arrived at camp, a bit tired

but exhilarated by the view at 12,000'. Judy was first in; Hughes was in

the back of the pack as usual. We rested in our tents for a couple of hours

(we really should have brought a book) until “tea” at about 3:30. Fredy

was somehow able to get (in the middle of nowhere!) a six pack of cokes

which some found more to our liking than instant coffee or teas.

In the morning some of us

made a quick hike up toward the summit of Dead Woman Pass before breakfast

for some early morning photos. After breakfast, we got no more than 100

yards from camp when the rain began and lasted all day. It was a tough

day for hiking: we climbed to the Pass and then dropped down to Pacaymayu

(a popular/crowded camp area with flush toilets) and then back up again

to Runkuracay, an Inca lookout post at over 12,000' with outstanding views

both down to the valley we’d just climbed from and out to the crest of

the Andes. (The photo on the right shows the trail from the top of the

pass down to Pacaymayu and up to near Runkuracay.) We continued to climb

up to nearly 13,000' before making camp at on the edge of the mountain

near some alpine ponds. In spite of the weather and the tough climb, we

made good time and not a one complained.

In the morning the cook

prepared a special birthday cake for one of our group and several of the

porters picked a huge bouquet of alpine flowers for her as well. It was

a very special occasion and may have accounted for a change in the weather

for the day: no rain! We left camp and climbed to Sayaqmarca (11,472')

a military city at a strategic site on the trail: great views and a defensible

position. Fredy gave us the history of the site and we walked leisurely

around the ruins before heading to  our

final camp near Puyupatamarca. Along the way, the vegetation changed from

alpine to a humid cloud forest environment with several varieties of orchids

mixed in with other flowers and lush greenery. Our camp that night (shown on the left)

was no less spectacular than the previous ones: views of the high peaks were

uninterrupted and dramatic, and we could look down on the town of Aguas

Calientes and Urubamba River over 3000' below.

our

final camp near Puyupatamarca. Along the way, the vegetation changed from

alpine to a humid cloud forest environment with several varieties of orchids

mixed in with other flowers and lush greenery. Our camp that night (shown on the left)

was no less spectacular than the previous ones: views of the high peaks were

uninterrupted and dramatic, and we could look down on the town of Aguas

Calientes and Urubamba River over 3000' below.

Our easiest day of hiking was our final

descent into Machu

Picchu: it was no more than five miles, almost all downhill, and the

rain that persisted throughout the morning and early afternoon stopped

just as we approached the western entrance, a suddenly near vertical stairway

to Intipunku, “The Doorway of the Sun.” Machu Picchu spread out beyond

and below us in all its drama and beauty. We had reached our goal and everyone

rejoiced for we knew that we were all within a half hour of the

Machu

Picchu Sanctuary Lodge, a 3–star accommodation with hot showers, fluffy

towels, a luxuriant queen size bed, and a bar with ice!

The spectacle of Machu Picchu

drew us in and we didn’t rush to the hotel. Rather we immersed ourselves

in the totality of the site: the remains of a major city and remarkable

architectural achievement that must rival any city in the world. The spire

of Huayna Picchu

(meaning “young peak”) in the background drew the attention of those of us who were planning to

make that difficult climb the next day. Finally, we gave in to the desire

for some creature comforts at the lodge and some much needed rest and change

into dry clothing. Pisco sours, wine, and beer preceded a fine dinner while

we told stories and recounted all we had seen and done for the past four

days. Needless to say, we all felt a great sense of accomplishment.

in the background drew the attention of those of us who were planning to

make that difficult climb the next day. Finally, we gave in to the desire

for some creature comforts at the lodge and some much needed rest and change

into dry clothing. Pisco sours, wine, and beer preceded a fine dinner while

we told stories and recounted all we had seen and done for the past four

days. Needless to say, we all felt a great sense of accomplishment.

A wake–up call at 5:00 am

got us up to view the ruins as the sun came up, a sacrifice we gladly made

to see the light and clouds change the setting from moment to moment. After

breakfast, Fredy, who had been a guide at Machu Picchu a few years earlier,

dusted off his tour and introduced us to much of the ruins until midmorning,

when the group split into those who would continue to explore the city

ruins and those who would climb Huayna Picchu (the mountain that is often

mistaken for Machu Picchu, which is the mountain on which is carved out

the city itself). Ruth Wright, in her detailed and very useful The

Machu Picchu Guidebook (Johnson Books, Boulder: 2001), says

to plan one hour to the top and a half hour down with an additional two

hours or so to appreciate the views as well as the ruins on are on the

top of what appears to be an inaccessible mountain top. We must have hurried,

but we felt the accomplishment of the climb and were thankful for the occasional

rope or chain to help us up the the very steep and narrow stairs. Coming

down was as arduous as the climb!

We left that afternoon by

bus to the little town of Aguas

Calientes: five miles of zigzagging dirt road, though only a mile and

a half straight down, the distance run by a nine–year–old boy who met us

at every crossing, waved and yelled, and ran on, eventually meeting us

at the bottom to collect his gratuity for a fine performance that he really

earned. We ate lunch in Aguas Calientes and caught the trail for Cusco.

In Ollantaytambo, we switched over to a bus which didn’t seem to make the

trip any faster than the train, and we arrived after dark at our hotel.

The following day was spent

on our own—packing, shopping, resting, and getting ready to leave for

home. That evening we celebrated the third birthday on the trip: One of

our group turned 15, a very special birthday in Latin America.

A quinceanera

celebration marks the transition from childhood to womanhood. Cindy, with

the help of several others, planned an elaborate ceremony/party at the

hotel complete with candles, carnations, and music for dancing. It was

a highlight for us all.

Our final day in Peru was

spent flying a delayed flight to Lima, taking a quick tour of downtown

(clogged with incredible traffic, thick diesel fumes, and a gray sky that

was less than cheery) and the Gold Museum. Because of the late flight—a

common occurrence in Peruvian aviation—our visit was rushed. We finished

the evening with a splendid farewell dinner at what has to be Cindy’s favorite

Lima restaurant, La Rosa Nautica, perched on a pier on the Pacific Ocean.

The surroundings were elegant and the seafood was delicious.

And it let us forget what

was ahead for us all: the red–eye flight to Dallas–Ft. Worth and on to

Denver.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

Machu Picchu is worth every

nickel, every minor hardship, and every stone along the Inca Trail to see

it. While it is possible to arrive at the this incredible place by train

and bus, the hike—which can be done anywhere from 3–8 days, according

to various tour operators—is an experience unto itself and should not

be missed if at all possible. In our group we had two teenage girls who

never complained nor whined, even when cold and wet and tired (at least publicly).

There were several artificial hips and knees among us, in addition to marathon

runners  and rock climbers. Heck, Fredy and Percy,

our guides, make the trip more than a dozen times a year. Our strongest advice, if

you can possibly do it, do it!

and rock climbers. Heck, Fredy and Percy,

our guides, make the trip more than a dozen times a year. Our strongest advice, if

you can possibly do it, do it!

Our sincere thanks

Cindy for attracting “the right people” to make

our experience memorable; to Jim

and Austin who proved persistence and

inner strength count for plenty; to Merilee

and Lorilee who reminded us once again

that traveling with young people can be enriching and insightful; to

Jim and Patience

who share such wonderful experiences with their children (and who know how to shop); to

Joe, Sharon, Caroline, Alan, Cheryl who were,

like the others, cheerful, considerate, and great fun to be with for 16 days.

And to guides Fredy and

Percy who kept us moving, kept us organized,

and kept us informed every step of the way—we’re sorry you can’t be with us for

the “Pictures and Pisco Sours Party.” We’ll remember you all.

finally the last leg of 45 minutes

to Puerto

Maldonado, a town of about 30,000 situated on the Rio Madre de Dios

near the borders of Brasil and Bolivia. After three days at

the Lake Sandoval Lodge in the Amazon rain forest,

we returned to Cusco where we explored the city (of about 250,000) and

the Sacred

Valley for four days. A train took us up the Urubamba River to Kilometer

88 where we began our four day hike on

the Inca

Trail (called the most popular hike in the world)

to Machu

Picchu, the most visited attraction in South America. After two days

at the Inca city, we returned to Cusco by train and bus for a day of R

& R. On our final day we flew to Lima for a city tour and farewell

dinner before boarding the plane for Dallas–Ft. Worth and on to Denver.

finally the last leg of 45 minutes

to Puerto

Maldonado, a town of about 30,000 situated on the Rio Madre de Dios

near the borders of Brasil and Bolivia. After three days at

the Lake Sandoval Lodge in the Amazon rain forest,

we returned to Cusco where we explored the city (of about 250,000) and

the Sacred

Valley for four days. A train took us up the Urubamba River to Kilometer

88 where we began our four day hike on

the Inca

Trail (called the most popular hike in the world)

to Machu

Picchu, the most visited attraction in South America. After two days

at the Inca city, we returned to Cusco by train and bus for a day of R

& R. On our final day we flew to Lima for a city tour and farewell

dinner before boarding the plane for Dallas–Ft. Worth and on to Denver.

excellent. More important to us, the trip she described involved hiking the Inca Trail

in order to enter Machu Picchu. She explained that, in addition to all

we would experience along the hike, the benefit of this was the opportunity

to spend more time at the site, especially in the evening and at sunrise

when there were not the crowds who were bused in each morning and who were

bused out mid–afternoon. We would, of course, have to camp, sleep on the

ground, carry a day pack, have the benefit of guides and porters (to carry

the tents, equipment, propane tanks, etc.). It seemed like exactly what

we were looking for in a trip: new places, exercise, and a group leader

like Cindy, who was organized and great fun to be with. While we couldn’t

go in 2000, we put ourselves on the list for 2001.

excellent. More important to us, the trip she described involved hiking the Inca Trail

in order to enter Machu Picchu. She explained that, in addition to all

we would experience along the hike, the benefit of this was the opportunity

to spend more time at the site, especially in the evening and at sunrise

when there were not the crowds who were bused in each morning and who were

bused out mid–afternoon. We would, of course, have to camp, sleep on the

ground, carry a day pack, have the benefit of guides and porters (to carry

the tents, equipment, propane tanks, etc.). It seemed like exactly what

we were looking for in a trip: new places, exercise, and a group leader

like Cindy, who was organized and great fun to be with. While we couldn’t

go in 2000, we put ourselves on the list for 2001.

deep in the heart of the southern region of the

great Amazon basin. Puerto Maldonado sits isolated on the banks of the muddy Rio

Madre de Dios which, like hundreds of other rivers on the east slope of the Andes,

eventually makes its way to the great Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean.

deep in the heart of the southern region of the

great Amazon basin. Puerto Maldonado sits isolated on the banks of the muddy Rio

Madre de Dios which, like hundreds of other rivers on the east slope of the Andes,

eventually makes its way to the great Amazon and the Atlantic Ocean.

(vultures, egrets,

(vultures, egrets,

There are reminders of the Incas throughout the city of Cusco. When the

Spanish arrived in 1533 it was a city as modern as most any in the world; within

a few brief years, churches were built from (and on) Inca walls and temples

in a concentrated effort to destroy the old gods and create a Spanish colonial

town on the ruins of the Inca capital. The cathedral of Cusco (shown on the left and below)

faces the Plaza de Armas in the center of the city. In 1983 it was, along with Machu Picchu,

the first of ten locations in Peru to be declared

a

There are reminders of the Incas throughout the city of Cusco. When the

Spanish arrived in 1533 it was a city as modern as most any in the world; within

a few brief years, churches were built from (and on) Inca walls and temples

in a concentrated effort to destroy the old gods and create a Spanish colonial

town on the ruins of the Inca capital. The cathedral of Cusco (shown on the left and below)

faces the Plaza de Armas in the center of the city. In 1983 it was, along with Machu Picchu,

the first of ten locations in Peru to be declared

a  primarily

several of the 40+ churches that serve the residents of Cusco, including

Santo Domingo with its Spanish wall built upon the huge Inca stones so

carefully carved, notched, and set smoothly upon each other; San Blas with

its ornate wood pulpit so intricately carved; and the cathedral which is

undergoing extensive renovation, a project of several years and many millions

of soles (financed in large part by the Peruvian telephone company which,

we were assured, accounted for why the telephone rates were so high). We

had hoped to see, in addition to the gold and silver altar pieces and fine

sculptures, the Spanish–Inca rendition of the Last Supper painted in part

by a traditional Spanish master, and in part by local Quechua painters

who painted in a local delicacy,

primarily

several of the 40+ churches that serve the residents of Cusco, including

Santo Domingo with its Spanish wall built upon the huge Inca stones so

carefully carved, notched, and set smoothly upon each other; San Blas with

its ornate wood pulpit so intricately carved; and the cathedral which is

undergoing extensive renovation, a project of several years and many millions

of soles (financed in large part by the Peruvian telephone company which,

we were assured, accounted for why the telephone rates were so high). We

had hoped to see, in addition to the gold and silver altar pieces and fine

sculptures, the Spanish–Inca rendition of the Last Supper painted in part

by a traditional Spanish master, and in part by local Quechua painters

who painted in a local delicacy,  The next two days were spent outside Cusco visiting important Inca

sites with our guide, Fredy Delgado, who would be with us the rest of the trip. On

Sunday, July 1, we headed to Ollantaytambo, a fortress–city on the Urubamba

River about 45 miles northwest of Cusco. On the way, we passed the Sunday

market in the small town of

The next two days were spent outside Cusco visiting important Inca

sites with our guide, Fredy Delgado, who would be with us the rest of the trip. On

Sunday, July 1, we headed to Ollantaytambo, a fortress–city on the Urubamba

River about 45 miles northwest of Cusco. On the way, we passed the Sunday

market in the small town of  pigs skittering about the floor (future dinners, perhaps?), skulls of family

members on a cornice shelf, and an

pigs skittering about the floor (future dinners, perhaps?), skulls of family

members on a cornice shelf, and an  as

the local guides suggest in a smarmy helpful way). The enormous walls are

comprised of massive granite monoliths that measure up to 16 feet high

and wide and weight up to 130 tons; it is a testimony to the engineering

genius of the Incas that they were able to cut, move, and place these stones

with the kind of precision that remains. There are a number of theories

regarding the purpose of the site: was it a castle? a fortress? a fortified

temple and city? or a complex suburb of Cusco? Whatever it was, what remains

staggers the imagination to explain how it came to be constructed. Walking

among the remaining walls is to walk as an ant in a boulder field. Along

with the massive ruins at Ollantaytambo, Saqsaywaman gave us a glimpse

of what we were to find at Machu Picchu and along the four day hike on

the Inca Trail.

as

the local guides suggest in a smarmy helpful way). The enormous walls are

comprised of massive granite monoliths that measure up to 16 feet high

and wide and weight up to 130 tons; it is a testimony to the engineering

genius of the Incas that they were able to cut, move, and place these stones

with the kind of precision that remains. There are a number of theories

regarding the purpose of the site: was it a castle? a fortress? a fortified

temple and city? or a complex suburb of Cusco? Whatever it was, what remains

staggers the imagination to explain how it came to be constructed. Walking

among the remaining walls is to walk as an ant in a boulder field. Along

with the massive ruins at Ollantaytambo, Saqsaywaman gave us a glimpse

of what we were to find at Machu Picchu and along the four day hike on

the Inca Trail.

(Dead

Woman Pass) the highest pass on the Trail at 13,780'. We stopped for a

short rest at Willkaraqay, a pre–Spanish village—the last place to buy

anything, we thought—and pushed ever upwards along the wide stone trail.

A couple of our group completed the 2–3 mile leg of the trip by horseback!

The air was thin, and the views of the snow–capped peaks were breathtaking.

We stopped for lunch about 11:15 at a table set up before our arrival by

the cooks and a few porters (the rest had gone on to set up camp at Llulluchapampa)

overlooking the valley from which we had just climbed. Another hour of

ascent through a lush cloud forest and we arrived at camp, a bit tired

but exhilarated by the view at 12,000'. Judy was first in; Hughes was in

the back of the pack as usual. We rested in our tents for a couple of hours

(we really should have brought a book) until “tea” at about 3:30. Fredy

was somehow able to get (in the middle of nowhere!) a six pack of cokes

which some found more to our liking than instant coffee or teas.

(Dead

Woman Pass) the highest pass on the Trail at 13,780'. We stopped for a

short rest at Willkaraqay, a pre–Spanish village—the last place to buy

anything, we thought—and pushed ever upwards along the wide stone trail.

A couple of our group completed the 2–3 mile leg of the trip by horseback!

The air was thin, and the views of the snow–capped peaks were breathtaking.

We stopped for lunch about 11:15 at a table set up before our arrival by

the cooks and a few porters (the rest had gone on to set up camp at Llulluchapampa)

overlooking the valley from which we had just climbed. Another hour of

ascent through a lush cloud forest and we arrived at camp, a bit tired

but exhilarated by the view at 12,000'. Judy was first in; Hughes was in

the back of the pack as usual. We rested in our tents for a couple of hours

(we really should have brought a book) until “tea” at about 3:30. Fredy

was somehow able to get (in the middle of nowhere!) a six pack of cokes

which some found more to our liking than instant coffee or teas.

our

final camp near Puyupatamarca. Along the way, the vegetation changed from

alpine to a humid cloud forest environment with several varieties of orchids

mixed in with other flowers and lush greenery. Our camp that night (shown on the left)

was no less spectacular than the previous ones: views of the high peaks were

uninterrupted and dramatic, and we could look down on the town of Aguas

Calientes and Urubamba River over 3000' below.

our

final camp near Puyupatamarca. Along the way, the vegetation changed from

alpine to a humid cloud forest environment with several varieties of orchids

mixed in with other flowers and lush greenery. Our camp that night (shown on the left)

was no less spectacular than the previous ones: views of the high peaks were

uninterrupted and dramatic, and we could look down on the town of Aguas

Calientes and Urubamba River over 3000' below.

in the background drew the attention of those of us who were planning to

make that difficult climb the next day. Finally, we gave in to the desire

for some creature comforts at the lodge and some much needed rest and change

into dry clothing. Pisco sours, wine, and beer preceded a fine dinner while

we told stories and recounted all we had seen and done for the past four

days. Needless to say, we all felt a great sense of accomplishment.

in the background drew the attention of those of us who were planning to

make that difficult climb the next day. Finally, we gave in to the desire

for some creature comforts at the lodge and some much needed rest and change

into dry clothing. Pisco sours, wine, and beer preceded a fine dinner while

we told stories and recounted all we had seen and done for the past four

days. Needless to say, we all felt a great sense of accomplishment.

and rock climbers. Heck, Fredy and Percy,

our guides, make the trip more than a dozen times a year. Our strongest advice, if

you can possibly do it, do it!

and rock climbers. Heck, Fredy and Percy,

our guides, make the trip more than a dozen times a year. Our strongest advice, if

you can possibly do it, do it!