BARRANCAS DEL COBRE

COPPER CANYON, MEXICO

May 6--13, 1998

THE BIG PICTURE

Barrancas del Cobre National Park, or

Copper Canyon, is a broad network of deep canyons in the mountainous state of

Chihuahua,

just south of the Texas and New Mexico borders. We flew from Denver to

Dallas-Fort Worth and then to Chihuahua City.

We took a van for the four-hour drive to the Sierra Lodge 15 miles from

Creel.

Two days later we drove about six hours and 6,000 feet down to the bottom

of the canyon to the town of Batopilas

where we stayed at the Riverside Lodge for four nights. We returned to

the Sierra Lodge for one night and then back to Chihuahua for the return

flight to Dallas-Fort Worth and Denver.

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE ADVENTURE

This trip started with a series of romantic images: of a

network of canyons deeper, wider, and more expansive than

Arizona's Grand Canyon; of barefoot running

Tarahumara

Indians surviving as traditional farmers in a still isolated part Mexico's

Sierra Madre Mountains ("Tarahumara" is apparently a corruption of Raramuri,

the name they call themselves. Raramuri translates as "the runners," "the

light footed ones," or "the footrunners," all of which make reference to

their ancestral tradition of running); of fabulous silver mines

that made Mexico the object of conquest by the Spanish; of a mysterious

and beautiful church ("The Lost Cathedral of Satevo") built, some

say, 350 years ago at the bottom of the Canyon in an area where very few

people have ever lived; and, more recently, of a gracious hacienda in the

isolated former mining village of Batopilas that had been lavishly restored

into a very comfortable and visually sumptuous lodge by an American from

Michigan who fell in love with the beauty of the area. When we called

Copper Canyon Lodges

to find out rates and availability, we discovered to our delight that the

first week of off season rates were remarkably attractive and we jumped

at the opportunity. We had no idea what a fortunate decision we had made.

Arizona's Grand Canyon; of barefoot running

Tarahumara

Indians surviving as traditional farmers in a still isolated part Mexico's

Sierra Madre Mountains ("Tarahumara" is apparently a corruption of Raramuri,

the name they call themselves. Raramuri translates as "the runners," "the

light footed ones," or "the footrunners," all of which make reference to

their ancestral tradition of running); of fabulous silver mines

that made Mexico the object of conquest by the Spanish; of a mysterious

and beautiful church ("The Lost Cathedral of Satevo") built, some

say, 350 years ago at the bottom of the Canyon in an area where very few

people have ever lived; and, more recently, of a gracious hacienda in the

isolated former mining village of Batopilas that had been lavishly restored

into a very comfortable and visually sumptuous lodge by an American from

Michigan who fell in love with the beauty of the area. When we called

Copper Canyon Lodges

to find out rates and availability, we discovered to our delight that the

first week of off season rates were remarkably attractive and we jumped

at the opportunity. We had no idea what a fortunate decision we had made.

SIERRA LODGE (Cabanas Canon Del

Cobre)

The drive from Chihuahua

City to Cusarare, home to the Sierra

Lodge, took us on a good highway to Cuauhtemoc,

through productive agricultural areas farmed by several generations of

immigrant Mennonites; then onto a secondary highway (i.e., paved but bumpy)

through San Juanito (a lumber center

our driver said was the ugliest city in all of Mexico) to

Creel,

a growing adventure-tourist town on the

Chihuahua al Pacifico Railroad (completed in 1961),

and an important stop on the magnificent

train ride from Los Mochis near the Sea of Cortez to Chihuahua City. Another

15 miles beyond is Cusarare, the mission village closest the Sierra Lodge.

The Sierra Lodge was built on property owned by the

Tarahumaras who continue to live

traditionally around the few acres that is rented

by the Lodge. Many Tarahumaras work at the Lodge or sell their baskets,

carvings, and weaving to guests. The original name was "Cabanas Canon del

Cobre" and the old sign remains. The dozen or so rooms have the charm of

another era of Mexico tourism. We are certain, however, the Sierra Lodge

is far more comfortable than Cabanas Canon del Cobre was in the 1940s or

1950s. Though there is still no electricity, the kerosene lamps gave ample

light in the rooms and dining hall, and battery powered reading lights

are provided to guests who wish to read after dark. A cedar log fire was

lit each evening while we were at dinner--for visual effect, for the incomparable

aroma, and to chase the slight chill out of the room; coffee, tea, or hot

chocolate

were brought to the room in the morning as a gentle way to wake up, although

we usually heard the donkeys, pigs, dogs, and chickens that wandered over

from the neighboring farms well before the soft knock of the woman who

brought the coffee. The dining room served meals, snacks,

margaritas, cold beer, and is a meeting place to recount the adventures of the day.

Tarahumaras who continue to live

traditionally around the few acres that is rented

by the Lodge. Many Tarahumaras work at the Lodge or sell their baskets,

carvings, and weaving to guests. The original name was "Cabanas Canon del

Cobre" and the old sign remains. The dozen or so rooms have the charm of

another era of Mexico tourism. We are certain, however, the Sierra Lodge

is far more comfortable than Cabanas Canon del Cobre was in the 1940s or

1950s. Though there is still no electricity, the kerosene lamps gave ample

light in the rooms and dining hall, and battery powered reading lights

are provided to guests who wish to read after dark. A cedar log fire was

lit each evening while we were at dinner--for visual effect, for the incomparable

aroma, and to chase the slight chill out of the room; coffee, tea, or hot

chocolate

were brought to the room in the morning as a gentle way to wake up, although

we usually heard the donkeys, pigs, dogs, and chickens that wandered over

from the neighboring farms well before the soft knock of the woman who

brought the coffee. The dining room served meals, snacks,

margaritas, cold beer, and is a meeting place to recount the adventures of the day.

One of the "room" options is sleeping in "the cave," which is a short walk

from the Lodge. Under the rock overhang that likely was used by Tarahumaras

in the past is a sand floor with beds, a bedside table, kerosene lamp,

rugs, and robes--all the comforts of the Lodge rooms except for the fire

place and bathroom facilities (yes, coffee is served there in the morning).

Guests can also arrange for overnight camping in the nearby hills.

One of the "room" options is sleeping in "the cave," which is a short walk

from the Lodge. Under the rock overhang that likely was used by Tarahumaras

in the past is a sand floor with beds, a bedside table, kerosene lamp,

rugs, and robes--all the comforts of the Lodge rooms except for the fire

place and bathroom facilities (yes, coffee is served there in the morning).

Guests can also arrange for overnight camping in the nearby hills.

At 7,000 feet, the night

sky was clear and crisp, but the days were sunny and warm for hiking and

seeking out waterfalls and swimming holes that, at other times of the year,

flow with great force. We spent our first full day hiking with another

couple and a guide throughout the adjoining

ejido, the lands held in common by the Tarahumaras.

The history of these remarkable people is, like the  history of all peoples native to the Americas, both heroic and tragic. That their

culture has persisted since the late 1500s when the Spanish (and later

the Mexicans) forced a foreign culture and religion upon them, is a story

of great heroism and of the will to survive. They have been called "the

least-assimilated people in North America." The difficulties these proud

people continue to experience as western culture and economics intrude

on their way of life maintains the tragedy. We read Richard D. Fisher's

Mexico's Copper Canyon (Sunracer

Publications, 1996) for a respectful, introductory history of the Tarahumaras

along with articles on the area as it was and as it has become in modern times.

history of all peoples native to the Americas, both heroic and tragic. That their

culture has persisted since the late 1500s when the Spanish (and later

the Mexicans) forced a foreign culture and religion upon them, is a story

of great heroism and of the will to survive. They have been called "the

least-assimilated people in North America." The difficulties these proud

people continue to experience as western culture and economics intrude

on their way of life maintains the tragedy. We read Richard D. Fisher's

Mexico's Copper Canyon (Sunracer

Publications, 1996) for a respectful, introductory history of the Tarahumaras

along with articles on the area as it was and as it has become in modern times.

Except in the vicinity

of the Sierra Lodge, we seldom saw any of the residents of the few and

scattered dwellings (both houses and the traditional stone cave huts that

are occasionally still used). Since we were there during the dry season,

there was little growing. We could only imagine what the area was like

when the rains came and created a green countryside where we saw only browns

and yellows. The waterfalls were only small trickles while we were there,

though it was easy to imagine their size during the wet season. We enjoyed

hiking this area of pinons and rocks and creeks. Finding a badly weathered

3" wooden ball along a distant trail reminded us of the "ball races" that

are central to Tarahumara tradition. We enjoyed getting to know the 21

other folks who would be traveling with us for the next week. We enjoyed

trail running at the end of the days. But it was the bottom of the canyon

we had come to explore.

THE TRIP DOWN

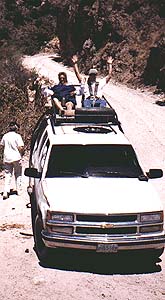

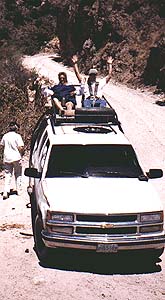

Getting down to the bottom of the canyon was an adventure by itself.

We began by strapping ourselves into

the two seats bolted to the top of a Chevy Suburban! If you make the trip yourself,

do not hesitate: Fight for a seat on the top! It's worth every skipped

heartbeat. Harness yourself to those seats and hang on for the ride of

your life. For the next 5-6 hours, we rode through small Tarahumara and

Mexican villages, passed by fields and orchards, crossed dry creeks and

sloping hills. The road for the first couple of hours was paved or well

graded. Then we come to the edge of

Batopi las Canyon and looked down one vertical mile to a tiny

ribbon of water which is Rio Batopilas.

What really took away our breath was the narrow, rutted, and very steep dirt

road that winds

the two seats bolted to the top of a Chevy Suburban! If you make the trip yourself,

do not hesitate: Fight for a seat on the top! It's worth every skipped

heartbeat. Harness yourself to those seats and hang on for the ride of

your life. For the next 5-6 hours, we rode through small Tarahumara and

Mexican villages, passed by fields and orchards, crossed dry creeks and

sloping hills. The road for the first couple of hours was paved or well

graded. Then we come to the edge of

Batopi las Canyon and looked down one vertical mile to a tiny

ribbon of water which is Rio Batopilas.

What really took away our breath was the narrow, rutted, and very steep dirt

road that winds and switch-backs its way 5,500 feet to the bridge that crosses to the other

side of the river. Our driver makes this trip almost daily and we, of necessity,

trusted him with our lives. (And he does have a lovely family in Cuauhtemoc

whom we met on the trip in from the airport.) From our perches atop the van,

we could see forever. It was like viewing it all from an airplane, though the

ruts and bumps in the road, not to mention the dust, told us otherwise.

and switch-backs its way 5,500 feet to the bridge that crosses to the other

side of the river. Our driver makes this trip almost daily and we, of necessity,

trusted him with our lives. (And he does have a lovely family in Cuauhtemoc

whom we met on the trip in from the airport.) From our perches atop the van,

we could see forever. It was like viewing it all from an airplane, though the

ruts and bumps in the road, not to mention the dust, told us otherwise.

We met two trucks hauling

supplies up from the bottom, probably from Batopilas since that's the only

town of any size in the bottom of the canyon. It was a miracle of inches

that one of us didn't go over the edge. Once down at the level of the river,

the road was no better nor wider, only flatter. We passed three settlements

that appear on maps (Basigochi,

Quirare, and

La Bufa), but the number of folks

living there could not total much more than a dozen. On the other side

of the Rio Batopilas was the trail that once was the only link to Batopilas

from "outside," and it is still used today. Along the way we found a shady

place just wide enough for two vehicles to pass, where the driver stopped

to build a fire in the road and fix burritos and frijoles for lunch.

We bumped along for another

couple of hours until we crossed one final bridge and read a welcome sign:

"Bienvenidos Amigos Visitantes."The English

translation continued: "You are entering to a hidden town of Mexico

full of history and friendly people. Founded in 1632. Population 1160.

Altitude 1650 feet. Subtropical Climate."

This was, for all

we could see--and were later to verify--the end of the road: Batopilas.

BATOPILAS

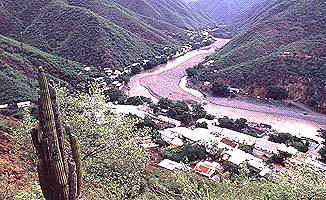

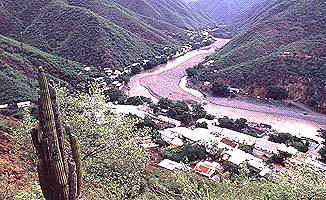

It's difficult to describe

Batopilas.

We don't have many frames of reference, though we've been at the bottom

of the Grand Canyon, Kings Canyon, and Yosemite. If you've been there,

imagine yourself at the bottom of the Grand Canyon and coming suddenly

upon 1,000 folks living in a town of modest but well maintained houses

clinging to a narrow, one mile stretch of river shoreline, where the large

and recently whitewashed church stands with doors open on to the town plaza,

and where along the narrow paved  main street there stands, just across from the church, a building that makes

you think of a small palace sparkling with colors, with gaily painted fountains

and light posts, and surrounded by a wall of stucco and tiles. It seemed

both out of place in its newness and beauty, yet quite at home within the

town as we imagined it did over a century ago when Batopilas was the second

most important silver mining town in Mexico. This was our destination, our

main street there stands, just across from the church, a building that makes

you think of a small palace sparkling with colors, with gaily painted fountains

and light posts, and surrounded by a wall of stucco and tiles. It seemed

both out of place in its newness and beauty, yet quite at home within the

town as we imagined it did over a century ago when Batopilas was the second

most important silver mining town in Mexico. This was our destination, our

Shangri-La for the next four nights:

the Riverside Lodge of Batopilas (shown on the left facing the main street),

where we dined in great comfort, slept in outstanding accommodations (in fact,

we were delighted to be assigned the "honeymoon suite"), where we witnessed

the most unexpected and festive wedding imaginable, and came to know some of

the most remarkable people with whom we've ever traveled.

Shangri-La for the next four nights:

the Riverside Lodge of Batopilas (shown on the left facing the main street),

where we dined in great comfort, slept in outstanding accommodations (in fact,

we were delighted to be assigned the "honeymoon suite"), where we witnessed

the most unexpected and festive wedding imaginable, and came to know some of

the most remarkable people with whom we've ever traveled.

Across the river from the

town, like the ruins of an Irish castle, sits the tumbled adobe and stone

remains of the once glorious home and offices of

Alexander Shepherd,

who came from Washington, DC with his family and household

staff--nannies, teachers, servants, etc.--in 1880 to be the superintendent

of the mines in Batopilas. Through his energy and knowledge, combined with

local sweat and mining company money, he brought running water, sewage,

and a hydro-electric plant to this isolated town, all of which remain in use today.

What's to do in such

an isolated and tiny corner of the world? Plenty, and we were only able

to see and do a few of what other travelers who stay longer write about.

THE LOST CATHEDRAL OF SATEVO

Despite the heat of

the day, we felt the urge to do what the folks who've lived there forever

do: run. (Female runners are probably the exception in this area--Tarahumara

women did not traditionally participate in ball races--and, while folks

waved in a friendly way to us as we passed a house or truck, Judy probably

drew second looks after we passed. At least

one woman laughed as we passed by her window.) Though the roads to the south and west of

Batopilas make driving, at best, a severe challenge, they are fine for running.

Our usual destination was the tiny village of

Satevo, about four miles of dusty road down river from Batopilas.

There in Satevo

one woman laughed as we passed by her window.) Though the roads to the south and west of

Batopilas make driving, at best, a severe challenge, they are fine for running.

Our usual destination was the tiny village of

Satevo, about four miles of dusty road down river from Batopilas.

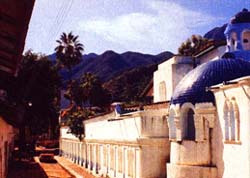

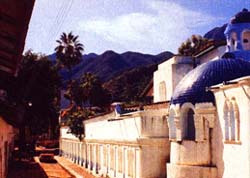

There in Satevo stands the remains of a church, sometimes referred to as "Templo de

Nuestra Senora de Satevo," said to have been built in the early 1600s; other sources

give it the name "Iglesias San Miguel de Satevo" and claim it was built

in the 1760s. Other names and dates appear elsewhere. Little seems to be

known for sure about who built it and why and who worshipped there. Hence,

its romantic name, "The Lost Cathedral." Efforts to restore this imposing,

traditional church have been irregular and without sustained funding. The

bullet holes from one "revolucion" or outlaw skirmish or another are visible

beneath the newly whitewashed exterior (at least on the front, shown on

the left with most of our group sitting in front of the entrance). The

doors are tall and heavy, and they could use additional coats of varnish

to protect against the alternating rains and sun. The interior walls once

displayed colorful frescos, but now are faded and chipped.

stands the remains of a church, sometimes referred to as "Templo de

Nuestra Senora de Satevo," said to have been built in the early 1600s; other sources

give it the name "Iglesias San Miguel de Satevo" and claim it was built

in the 1760s. Other names and dates appear elsewhere. Little seems to be

known for sure about who built it and why and who worshipped there. Hence,

its romantic name, "The Lost Cathedral." Efforts to restore this imposing,

traditional church have been irregular and without sustained funding. The

bullet holes from one "revolucion" or outlaw skirmish or another are visible

beneath the newly whitewashed exterior (at least on the front, shown on

the left with most of our group sitting in front of the entrance). The

doors are tall and heavy, and they could use additional coats of varnish

to protect against the alternating rains and sun. The interior walls once

displayed colorful frescos, but now are faded and chipped.

The few houses and

the single "store" (really the front room of one of the houses and sells

mostly cold sodas, beer, candy, and snacks) remind us that this is a very

isolated and sparsely populated corner of the canyon and always has been.

The people are used to outsiders visiting, though never many at a time.

Life continues at a leisurely pace, guided by the weather and not the arrival

of tourist buses. Come back in a hundred years and Satevo will be the same.

We can only hope the church will be standing for others to gaze upon and wonder.

THE MINES

The hillsides to the north

and west of Batopilas are dotted with holes, many dug a few feet just "on

spec." Others mark the opening of long tunnels out of which tons of silver

ore was carried out on the backs of men and burros, and in ore cars. We've

always been interested in mines, minerals, and mining history, so the

Batopilas mines

were one of the first places  we wanted to explore. We hired a local resident, Manuel, as a guide for

the day. He was a most courteous and soft-spoken gentleman who knew about

mines in the area and how to get there. In addition, he knew the name of

every plant along the way and enough English to tell us about each! The

three of us left just after breakfast with our water and sack lunches prepared

by the kitchen staff at the Riverside Lodge.

we wanted to explore. We hired a local resident, Manuel, as a guide for

the day. He was a most courteous and soft-spoken gentleman who knew about

mines in the area and how to get there. In addition, he knew the name of

every plant along the way and enough English to tell us about each! The

three of us left just after breakfast with our water and sack lunches prepared

by the kitchen staff at the Riverside Lodge.

Along the way, we'd ask

about some aspect of the history of mining in the area and about the plants

we passed. Manuel showed us how to recognize different cactuses

(cardon, bisnaga, cibite, and pitalla among others);

he pointed out papelillos, birch-like trees with paper bark; and despite

it being the dry season, there were still beautiful red flowers on both the

jaboncillo and tabachin

trees. We've seen photographs of the same hillside during and just after

the rainy season, and it looks as lush and green as a rain forest, but

the dry season may be best for hiking.

After a couple of hours

of trudging through dry washes and over old trails, we came around a corner

where we saw foundation ruins and, nearby, the opening of a tunnel of one

of the prosperous mines in the area. Unlike many abandoned mines in the Rockies,

this tunnel was dry for the half mile or so we walked. Huge beams supported

the walls and ceilings, and in one area, several beams had been wedged

between the bedrock and a huge overhanging rock slab. Though the rails

and ties that supported the ore cars had long been removed, toward the

back of the mine were scattered pieces of machinery and other signs that

there had been activity as recently as the early 1940s.

this tunnel was dry for the half mile or so we walked. Huge beams supported

the walls and ceilings, and in one area, several beams had been wedged

between the bedrock and a huge overhanging rock slab. Though the rails

and ties that supported the ore cars had long been removed, toward the

back of the mine were scattered pieces of machinery and other signs that

there had been activity as recently as the early 1940s.

Our return to town was via

a different route that gave us many opportunities for photographs overlooking

Batopilas and the river below. In all, we could never had enjoyed the day

without the patience and courtesy of Manuel.

THE RANCHES

Our second day of hiking

was as interesting as the hike to the mines, though for very different

reasons and under unanticipated circumstances.

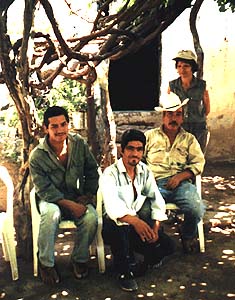

We took the opportunity

to visit, with another couple, a small, isolated ranch owned by the Pilar

family several miles above town. Our guide was a young American woman,

proficient in Spanish and kind of "on staff" with the Lodge, but new enough

to the area that she brought along a local man who knew the area, but who

spoke no English. It seemed like a good plan. However, not more than half

an hour into the hike up the trail/dry creek bed, the wife of the other

couple became sick and needed to turn back. Her husband thought he should

return with her. Our American guide went with them and the remaining three

of us pushed on in relative silence: one who spoke no English, and two

of us who wished we'd read the Spanish phrase book more carefully and more often.

We arrived hot and sweaty

at the complex of buildings--houses, barns, sheds, etc.--that

comprise the Pilar family ranch. We were welcomed by Sr. Pilar and his wife who

had swept her dirt floor spick and span and shooed out almost all the chickens

and dogs. We bought a round of cold sodas from her and we all sat outside

in the shade. We attracted some other family members who spoke some English.

They showed us around the ranch "headquarters" where Sra. Pilar and a grandmother

grew gorgeous flowers. (When we got home, Judy sent a supply of flower

seeds that they thought would do well in their garden.) One of the sons

showed us around the pens of the few goats, cows, pigs, and sheep they

kept. One of the young men (family member or ranch worker?) offered us an

envelope of recently harvested weed which we were assured was "Very fresh.

Very good." Though we still are not sure if it was for sale, or was a sample,

or a gesture of friendship, we declined with grace. "No fumar, gracias,"

we said in broken Spanish. But the event did answer one of the puzzles

we had on the hike up: Those really were marijuana plants along the trail

we saw from time to time, probably wind blown or bird carried from the

strangely still green cultivated area on a hillside above the ranch.

comprise the Pilar family ranch. We were welcomed by Sr. Pilar and his wife who

had swept her dirt floor spick and span and shooed out almost all the chickens

and dogs. We bought a round of cold sodas from her and we all sat outside

in the shade. We attracted some other family members who spoke some English.

They showed us around the ranch "headquarters" where Sra. Pilar and a grandmother

grew gorgeous flowers. (When we got home, Judy sent a supply of flower

seeds that they thought would do well in their garden.) One of the sons

showed us around the pens of the few goats, cows, pigs, and sheep they

kept. One of the young men (family member or ranch worker?) offered us an

envelope of recently harvested weed which we were assured was "Very fresh.

Very good." Though we still are not sure if it was for sale, or was a sample,

or a gesture of friendship, we declined with grace. "No fumar, gracias,"

we said in broken Spanish. But the event did answer one of the puzzles

we had on the hike up: Those really were marijuana plants along the trail

we saw from time to time, probably wind blown or bird carried from the

strangely still green cultivated area on a hillside above the ranch.

The most surprising sight,

however, was the 9' x 12' one room adobe and tin roof schoolhouse next

to the ranch workers' living quarters. We were invited in to watch a half

dozen elementary age kids and a twenty-something teacher (not a family

member) working on arithmetic lessons. There were textbooks, workbooks,

paper and pencils, a couple of wall maps, and a blackboard. Miles from

anywhere and government supplied, it was school as usual!

We got back in time to ride

with the rest of the group to a swimming hole in the Rio Batopilas a few

miles upstream from town. The water was cool and very refreshing on this

hot afternoon--and probably full of

giardia,

animal waste, and other unspeakable sickness producing elements! No one,

however, got the least bit sick and everyone wanted to come back again

the next day. We hiked back along the aqueduct that Shepherd had engineered

in the 1880s that had brought water to town and had generated a fairly reliable

supply of electricity for the mines and the town. Several folks who lived along

the route offered ripe mangoes and other fruits for sale as we passed.

THE WEDDING

There was among us a couple

about our age who was planning to marry the following October. But they

fell in love with Riverside Lodge and decided this was where they wanted to

marry. They also grew attached enough to the rest of us that they wanted

us to join in their celebration. This was not something they'd planned.

In fact, Irene made the snap decision on Sunday and the wedding took place

Monday evening.

We found out about it Monday

morning when, at our seats for breakfast, there were handwritten invitations

on Lodge stationary that said simply, "Dear Friends, You are invited to

attend the wedding of Irene Estrello and Dennis Metcalf at the Batopilas Riverside

Lodge in the Fountain Courtyard at 6 PM Monday, May 11, 1998. We would

be honored for you to share in this Beautiful, Blessed Ceremony. With love,

Irene and Dennis." Enclosed was a bougainvillea flower.

attend the wedding of Irene Estrello and Dennis Metcalf at the Batopilas Riverside

Lodge in the Fountain Courtyard at 6 PM Monday, May 11, 1998. We would

be honored for you to share in this Beautiful, Blessed Ceremony. With love,

Irene and Dennis." Enclosed was a bougainvillea flower.

We were excited, of course,

but also stunned that this American couple would try on a day's notice

to do all the necessary paperwork (and there were lots of papers involved),

find an official to do the marrying, plan the food and entertainment, rehearse

the ceremony, and all the rest that goes into a "proper" wedding. It couldn't

be done. Yet, to our delight they pulled it off and made the trip for everyone

an experience we shall not forget.

Dennis hired a band (not

the best musicians, but they were enthusiastic) and arranged for dinner

wines (though the bar was always open to guests). Somewhere, somehow, he

found a different baseball cap  for the older of Muff Curtiss's eleven kids. (Chris said he liked the caps,

but it was too bad that they wouldn't be able to wear them to school when

they got home because there was a marijuana plant on each one.) The chef

not only produced his usual fine dinner, but made a real wedding cake with

the appropriate decorations. Manolo, the manager of the Lodge, arranged

for a town clerk to make fast work of the bureaucratic hoops and paperwork.

He also arranged for the clerk to perform the ceremony. Manolo assisted

with the ceremony translation and made sure that afterward five witnesses

(Hughes was one) signed the myriad of legal documents in the proper place.

Gita, a very serious girl of about ten, agreed to be the flower girl and

just happened to have a stunning gold satin blouse with a black jumper

dress that lent the proper formal touch to the event. In fact, to our surprise,

just about everyone had something clean and "dressy" for the occasion.

for the older of Muff Curtiss's eleven kids. (Chris said he liked the caps,

but it was too bad that they wouldn't be able to wear them to school when

they got home because there was a marijuana plant on each one.) The chef

not only produced his usual fine dinner, but made a real wedding cake with

the appropriate decorations. Manolo, the manager of the Lodge, arranged

for a town clerk to make fast work of the bureaucratic hoops and paperwork.

He also arranged for the clerk to perform the ceremony. Manolo assisted

with the ceremony translation and made sure that afterward five witnesses

(Hughes was one) signed the myriad of legal documents in the proper place.

Gita, a very serious girl of about ten, agreed to be the flower girl and

just happened to have a stunning gold satin blouse with a black jumper

dress that lent the proper formal touch to the event. In fact, to our surprise,

just about everyone had something clean and "dressy" for the occasion.

We toasted the couple, we dined

and ate cake, we danced, we drank, we sang, we took pictures, we laughed, and

most

of all we felt fortunate to have been a part of this moment. We thanked

the staff of the Lodge for doing everything just right and with ease and

great grace. It was almost as though they'd done this a hundred times,

though Manolo said it was the first wedding on such short notice, that

usually people come already married and honeymoon there. Dennis set up

his camcorder and taped everything. A month or two after we got home, he

sent us a copy which gave us a chance to relive the memory once again.

Thank you, Dennis and Irene, for choosing the Riverside Lodge that week,

and for including us in your joy.

most

of all we felt fortunate to have been a part of this moment. We thanked

the staff of the Lodge for doing everything just right and with ease and

great grace. It was almost as though they'd done this a hundred times,

though Manolo said it was the first wedding on such short notice, that

usually people come already married and honeymoon there. Dennis set up

his camcorder and taped everything. A month or two after we got home, he

sent us a copy which gave us a chance to relive the memory once again.

Thank you, Dennis and Irene, for choosing the Riverside Lodge that week,

and for including us in your joy.

A LASTING RECOLLECTION

A few years before, we had

traveled with a group that included two of the absolutely worst behaved

children we have had the misfortune to be forced to be with. For one long

week, these two brothers, ages 12 and 14, were rude, obnoxious, hostile,

selfish, self-absorbed, bickering, loud, meanspirited, and without any

parental controls whatsoever. The dentist father absented himself whenever

there was confrontation between them or between them and the adults on

the trip. The mother was a licensed child psychologist--say no more! It was

the trip from hell. We vowed never to go on a group trip where there were kids.

You might begin to imagine

our horror when we learned that we would be spending the trip with not

two, but 11 kids, ages 5 to about 20, who were on the trip with their adoptive

mother and another woman escort. All of the kids, we were told, were "special"

in some way: severely retarded, learning delayed, emotionally disturbed,

hearing impaired, had some physical handicap, or some combination thereof.

This, we thought, could be the trip from hell times five!

Nothing could have been

farther from the truth. Nobody told us about Muff Curtiss (on the far right

in the flower print dress), a single mother of great wisdom, kindness, patience,

love, fortitude,

strength, backbone, and resolve, who created a loving home for

this biracial group of young people, who themselves have learned (or are

in the process of learning) self-respect, patience, kindness, courtesy,

caring, and the love of living from Muff. We cannot imagine a nicer group

of people with whom to travel. They turned an adventure trip into travel

with friends. Whatever Muff has--and if she were interested--she could

sell it by the bottle and put all the licensed child psychologists out

of business. She has found the secret of making a family out of a group,

and nurturing individuals who like themselves and, therefore, can care

for others. Thank you, Muff, Clara, Boo, J'Mari, Imani, Gita, Chris, Chen,

Emma, Maia (who was to graduate from high school the next month with honors!),

Josh, and Makana. We'll not forget each of you and all you taught us about

what a family can be. And we're still waiting to hear about your trip last

year (1999) to the Amazon!!

love, fortitude,

strength, backbone, and resolve, who created a loving home for

this biracial group of young people, who themselves have learned (or are

in the process of learning) self-respect, patience, kindness, courtesy,

caring, and the love of living from Muff. We cannot imagine a nicer group

of people with whom to travel. They turned an adventure trip into travel

with friends. Whatever Muff has--and if she were interested--she could

sell it by the bottle and put all the licensed child psychologists out

of business. She has found the secret of making a family out of a group,

and nurturing individuals who like themselves and, therefore, can care

for others. Thank you, Muff, Clara, Boo, J'Mari, Imani, Gita, Chris, Chen,

Emma, Maia (who was to graduate from high school the next month with honors!),

Josh, and Makana. We'll not forget each of you and all you taught us about

what a family can be. And we're still waiting to hear about your trip last

year (1999) to the Amazon!!

Other accounts of this same

outstanding trip can be found in guidebooks, magazine articles, promotional

brochures, and other places on the internet. Of course, none of those folks

met Muff Curtiss and her incredible kids, nor did they have a chance to dance

at Dennis and Irene's wedding. And that makes all the difference in the world.

Arizona's Grand Canyon; of barefoot running

Tarahumara

Indians surviving as traditional farmers in a still isolated part Mexico's

Sierra Madre Mountains ("Tarahumara" is apparently a corruption of Raramuri,

the name they call themselves. Raramuri translates as "the runners," "the

light footed ones," or "the footrunners," all of which make reference to

their ancestral tradition of running); of fabulous silver mines

that made Mexico the object of conquest by the Spanish; of a mysterious

and beautiful church ("The Lost Cathedral of Satevo") built, some

say, 350 years ago at the bottom of the Canyon in an area where very few

people have ever lived; and, more recently, of a gracious hacienda in the

isolated former mining village of Batopilas that had been lavishly restored

into a very comfortable and visually sumptuous lodge by an American from

Michigan who fell in love with the beauty of the area. When we called

Copper Canyon Lodges

to find out rates and availability, we discovered to our delight that the

first week of off season rates were remarkably attractive and we jumped

at the opportunity. We had no idea what a fortunate decision we had made.

Arizona's Grand Canyon; of barefoot running

Tarahumara

Indians surviving as traditional farmers in a still isolated part Mexico's

Sierra Madre Mountains ("Tarahumara" is apparently a corruption of Raramuri,

the name they call themselves. Raramuri translates as "the runners," "the

light footed ones," or "the footrunners," all of which make reference to

their ancestral tradition of running); of fabulous silver mines

that made Mexico the object of conquest by the Spanish; of a mysterious

and beautiful church ("The Lost Cathedral of Satevo") built, some

say, 350 years ago at the bottom of the Canyon in an area where very few

people have ever lived; and, more recently, of a gracious hacienda in the

isolated former mining village of Batopilas that had been lavishly restored

into a very comfortable and visually sumptuous lodge by an American from

Michigan who fell in love with the beauty of the area. When we called

Copper Canyon Lodges

to find out rates and availability, we discovered to our delight that the

first week of off season rates were remarkably attractive and we jumped

at the opportunity. We had no idea what a fortunate decision we had made.

Tarahumaras who continue to live

traditionally around the few acres that is rented

by the Lodge. Many Tarahumaras work at the Lodge or sell their baskets,

carvings, and weaving to guests. The original name was "Cabanas Canon del

Cobre" and the old sign remains. The dozen or so rooms have the charm of

another era of Mexico tourism. We are certain, however, the Sierra Lodge

is far more comfortable than Cabanas Canon del Cobre was in the 1940s or

1950s. Though there is still no electricity, the kerosene lamps gave ample

light in the rooms and dining hall, and battery powered reading lights

are provided to guests who wish to read after dark. A cedar log fire was

lit each evening while we were at dinner--for visual effect, for the incomparable

aroma, and to chase the slight chill out of the room; coffee, tea, or hot

Tarahumaras who continue to live

traditionally around the few acres that is rented

by the Lodge. Many Tarahumaras work at the Lodge or sell their baskets,

carvings, and weaving to guests. The original name was "Cabanas Canon del

Cobre" and the old sign remains. The dozen or so rooms have the charm of

another era of Mexico tourism. We are certain, however, the Sierra Lodge

is far more comfortable than Cabanas Canon del Cobre was in the 1940s or

1950s. Though there is still no electricity, the kerosene lamps gave ample

light in the rooms and dining hall, and battery powered reading lights

are provided to guests who wish to read after dark. A cedar log fire was

lit each evening while we were at dinner--for visual effect, for the incomparable

aroma, and to chase the slight chill out of the room; coffee, tea, or hot

One of the "room" options is sleeping in "the cave," which is a short walk

from the Lodge. Under the rock overhang that likely was used by Tarahumaras

in the past is a sand floor with beds, a bedside table, kerosene lamp,

rugs, and robes--all the comforts of the Lodge rooms except for the fire

place and bathroom facilities (yes, coffee is served there in the morning).

Guests can also arrange for overnight camping in the nearby hills.

One of the "room" options is sleeping in "the cave," which is a short walk

from the Lodge. Under the rock overhang that likely was used by Tarahumaras

in the past is a sand floor with beds, a bedside table, kerosene lamp,

rugs, and robes--all the comforts of the Lodge rooms except for the fire

place and bathroom facilities (yes, coffee is served there in the morning).

Guests can also arrange for overnight camping in the nearby hills.

history of all peoples native to the Americas, both heroic and tragic. That their

culture has persisted since the late 1500s when the Spanish (and later

the Mexicans) forced a foreign culture and religion upon them, is a story

of great heroism and of the will to survive. They have been called "the

least-assimilated people in North America." The difficulties these proud

people continue to experience as western culture and economics intrude

on their way of life maintains the tragedy. We read Richard D. Fisher's

Mexico's Copper Canyon (Sunracer

Publications, 1996) for a respectful, introductory history of the Tarahumaras

along with articles on the area as it was and as it has become in modern times.

history of all peoples native to the Americas, both heroic and tragic. That their

culture has persisted since the late 1500s when the Spanish (and later

the Mexicans) forced a foreign culture and religion upon them, is a story

of great heroism and of the will to survive. They have been called "the

least-assimilated people in North America." The difficulties these proud

people continue to experience as western culture and economics intrude

on their way of life maintains the tragedy. We read Richard D. Fisher's

Mexico's Copper Canyon (Sunracer

Publications, 1996) for a respectful, introductory history of the Tarahumaras

along with articles on the area as it was and as it has become in modern times.

the two seats bolted to the top of a Chevy Suburban! If you make the trip yourself,

do not hesitate: Fight for a seat on the top! It's worth every skipped

heartbeat. Harness yourself to those seats and hang on for the ride of

your life. For the next 5-6 hours, we rode through small Tarahumara and

Mexican villages, passed by fields and orchards, crossed dry creeks and

sloping hills. The road for the first couple of hours was paved or well

graded. Then we come to the edge of

the two seats bolted to the top of a Chevy Suburban! If you make the trip yourself,

do not hesitate: Fight for a seat on the top! It's worth every skipped

heartbeat. Harness yourself to those seats and hang on for the ride of

your life. For the next 5-6 hours, we rode through small Tarahumara and

Mexican villages, passed by fields and orchards, crossed dry creeks and

sloping hills. The road for the first couple of hours was paved or well

graded. Then we come to the edge of

and switch-backs its way 5,500 feet to the bridge that crosses to the other

side of the river. Our driver makes this trip almost daily and we, of necessity,

trusted him with our lives. (And he does have a lovely family in Cuauhtemoc

whom we met on the trip in from the airport.) From our perches atop the van,

we could see forever. It was like viewing it all from an airplane, though the

ruts and bumps in the road, not to mention the dust, told us otherwise.

and switch-backs its way 5,500 feet to the bridge that crosses to the other

side of the river. Our driver makes this trip almost daily and we, of necessity,

trusted him with our lives. (And he does have a lovely family in Cuauhtemoc

whom we met on the trip in from the airport.) From our perches atop the van,

we could see forever. It was like viewing it all from an airplane, though the

ruts and bumps in the road, not to mention the dust, told us otherwise.

main street there stands, just across from the church, a building that makes

you think of a small palace sparkling with colors, with gaily painted fountains

and light posts, and surrounded by a wall of stucco and tiles. It seemed

both out of place in its newness and beauty, yet quite at home within the

town as we imagined it did over a century ago when Batopilas was the second

most important silver mining town in Mexico. This was our destination, our

main street there stands, just across from the church, a building that makes

you think of a small palace sparkling with colors, with gaily painted fountains

and light posts, and surrounded by a wall of stucco and tiles. It seemed

both out of place in its newness and beauty, yet quite at home within the

town as we imagined it did over a century ago when Batopilas was the second

most important silver mining town in Mexico. This was our destination, our

Shangri-La for the next four nights:

the Riverside Lodge of Batopilas (shown on the left facing the main street),

where we dined in great comfort, slept in outstanding accommodations (in fact,

we were delighted to be assigned the "honeymoon suite"), where we witnessed

the most unexpected and festive wedding imaginable, and came to know some of

the most remarkable people with whom we've ever traveled.

Shangri-La for the next four nights:

the Riverside Lodge of Batopilas (shown on the left facing the main street),

where we dined in great comfort, slept in outstanding accommodations (in fact,

we were delighted to be assigned the "honeymoon suite"), where we witnessed

the most unexpected and festive wedding imaginable, and came to know some of

the most remarkable people with whom we've ever traveled.

one woman laughed as we passed by her window.) Though the roads to the south and west of

Batopilas make driving, at best, a severe challenge, they are fine for running.

Our usual destination was the tiny village of

one woman laughed as we passed by her window.) Though the roads to the south and west of

Batopilas make driving, at best, a severe challenge, they are fine for running.

Our usual destination was the tiny village of

stands the remains of a church, sometimes referred to as "Templo de

Nuestra Senora de Satevo," said to have been built in the early 1600s; other sources

give it the name "Iglesias San Miguel de Satevo" and claim it was built

in the 1760s. Other names and dates appear elsewhere. Little seems to be

known for sure about who built it and why and who worshipped there. Hence,

its romantic name, "The Lost Cathedral." Efforts to restore this imposing,

traditional church have been irregular and without sustained funding. The

bullet holes from one "revolucion" or outlaw skirmish or another are visible

beneath the newly whitewashed exterior (at least on the front, shown on

the left with most of our group sitting in front of the entrance). The

doors are tall and heavy, and they could use additional coats of varnish

to protect against the alternating rains and sun. The interior walls once

displayed colorful frescos, but now are faded and chipped.

stands the remains of a church, sometimes referred to as "Templo de

Nuestra Senora de Satevo," said to have been built in the early 1600s; other sources

give it the name "Iglesias San Miguel de Satevo" and claim it was built

in the 1760s. Other names and dates appear elsewhere. Little seems to be

known for sure about who built it and why and who worshipped there. Hence,

its romantic name, "The Lost Cathedral." Efforts to restore this imposing,

traditional church have been irregular and without sustained funding. The

bullet holes from one "revolucion" or outlaw skirmish or another are visible

beneath the newly whitewashed exterior (at least on the front, shown on

the left with most of our group sitting in front of the entrance). The

doors are tall and heavy, and they could use additional coats of varnish

to protect against the alternating rains and sun. The interior walls once

displayed colorful frescos, but now are faded and chipped.

we wanted to explore. We hired a local resident, Manuel, as a guide for

the day. He was a most courteous and soft-spoken gentleman who knew about

mines in the area and how to get there. In addition, he knew the name of

every plant along the way and enough English to tell us about each! The

three of us left just after breakfast with our water and sack lunches prepared

by the kitchen staff at the Riverside Lodge.

we wanted to explore. We hired a local resident, Manuel, as a guide for

the day. He was a most courteous and soft-spoken gentleman who knew about

mines in the area and how to get there. In addition, he knew the name of

every plant along the way and enough English to tell us about each! The

three of us left just after breakfast with our water and sack lunches prepared

by the kitchen staff at the Riverside Lodge.

this tunnel was dry for the half mile or so we walked. Huge beams supported

the walls and ceilings, and in one area, several beams had been wedged

between the bedrock and a huge overhanging rock slab. Though the rails

and ties that supported the ore cars had long been removed, toward the

back of the mine were scattered pieces of machinery and other signs that

there had been activity as recently as the early 1940s.

this tunnel was dry for the half mile or so we walked. Huge beams supported

the walls and ceilings, and in one area, several beams had been wedged

between the bedrock and a huge overhanging rock slab. Though the rails

and ties that supported the ore cars had long been removed, toward the

back of the mine were scattered pieces of machinery and other signs that

there had been activity as recently as the early 1940s.

comprise the Pilar family ranch. We were welcomed by Sr. Pilar and his wife who

had swept her dirt floor spick and span and shooed out almost all the chickens

and dogs. We bought a round of cold sodas from her and we all sat outside

in the shade. We attracted some other family members who spoke some English.

They showed us around the ranch "headquarters" where Sra. Pilar and a grandmother

grew gorgeous flowers. (When we got home, Judy sent a supply of flower

seeds that they thought would do well in their garden.) One of the sons

showed us around the pens of the few goats, cows, pigs, and sheep they

kept. One of the young men (family member or ranch worker?) offered us an

envelope of recently harvested weed which we were assured was "Very fresh.

Very good." Though we still are not sure if it was for sale, or was a sample,

or a gesture of friendship, we declined with grace. "No fumar, gracias,"

we said in broken Spanish. But the event did answer one of the puzzles

we had on the hike up: Those really were marijuana plants along the trail

we saw from time to time, probably wind blown or bird carried from the

strangely still green cultivated area on a hillside above the ranch.

comprise the Pilar family ranch. We were welcomed by Sr. Pilar and his wife who

had swept her dirt floor spick and span and shooed out almost all the chickens

and dogs. We bought a round of cold sodas from her and we all sat outside

in the shade. We attracted some other family members who spoke some English.

They showed us around the ranch "headquarters" where Sra. Pilar and a grandmother

grew gorgeous flowers. (When we got home, Judy sent a supply of flower

seeds that they thought would do well in their garden.) One of the sons

showed us around the pens of the few goats, cows, pigs, and sheep they

kept. One of the young men (family member or ranch worker?) offered us an

envelope of recently harvested weed which we were assured was "Very fresh.

Very good." Though we still are not sure if it was for sale, or was a sample,

or a gesture of friendship, we declined with grace. "No fumar, gracias,"

we said in broken Spanish. But the event did answer one of the puzzles

we had on the hike up: Those really were marijuana plants along the trail

we saw from time to time, probably wind blown or bird carried from the

strangely still green cultivated area on a hillside above the ranch.

attend the wedding of Irene Estrello and Dennis Metcalf at the Batopilas Riverside

Lodge in the Fountain Courtyard at 6 PM Monday, May 11, 1998. We would

be honored for you to share in this Beautiful, Blessed Ceremony. With love,

Irene and Dennis." Enclosed was a bougainvillea flower.

attend the wedding of Irene Estrello and Dennis Metcalf at the Batopilas Riverside

Lodge in the Fountain Courtyard at 6 PM Monday, May 11, 1998. We would

be honored for you to share in this Beautiful, Blessed Ceremony. With love,

Irene and Dennis." Enclosed was a bougainvillea flower.

for the older of Muff Curtiss's eleven kids. (Chris said he liked the caps,

but it was too bad that they wouldn't be able to wear them to school when

they got home because there was a marijuana plant on each one.) The chef

not only produced his usual fine dinner, but made a real wedding cake with

the appropriate decorations. Manolo, the manager of the Lodge, arranged

for a town clerk to make fast work of the bureaucratic hoops and paperwork.

He also arranged for the clerk to perform the ceremony. Manolo assisted

with the ceremony translation and made sure that afterward five witnesses

(Hughes was one) signed the myriad of legal documents in the proper place.

Gita, a very serious girl of about ten, agreed to be the flower girl and

just happened to have a stunning gold satin blouse with a black jumper

dress that lent the proper formal touch to the event. In fact, to our surprise,

just about everyone had something clean and "dressy" for the occasion.

for the older of Muff Curtiss's eleven kids. (Chris said he liked the caps,

but it was too bad that they wouldn't be able to wear them to school when

they got home because there was a marijuana plant on each one.) The chef

not only produced his usual fine dinner, but made a real wedding cake with

the appropriate decorations. Manolo, the manager of the Lodge, arranged

for a town clerk to make fast work of the bureaucratic hoops and paperwork.

He also arranged for the clerk to perform the ceremony. Manolo assisted

with the ceremony translation and made sure that afterward five witnesses

(Hughes was one) signed the myriad of legal documents in the proper place.

Gita, a very serious girl of about ten, agreed to be the flower girl and

just happened to have a stunning gold satin blouse with a black jumper

dress that lent the proper formal touch to the event. In fact, to our surprise,

just about everyone had something clean and "dressy" for the occasion.

most

of all we felt fortunate to have been a part of this moment. We thanked

the staff of the Lodge for doing everything just right and with ease and

great grace. It was almost as though they'd done this a hundred times,

though Manolo said it was the first wedding on such short notice, that

usually people come already married and honeymoon there. Dennis set up

his camcorder and taped everything. A month or two after we got home, he

sent us a copy which gave us a chance to relive the memory once again.

Thank you, Dennis and Irene, for choosing the Riverside Lodge that week,

and for including us in your joy.

most

of all we felt fortunate to have been a part of this moment. We thanked

the staff of the Lodge for doing everything just right and with ease and

great grace. It was almost as though they'd done this a hundred times,

though Manolo said it was the first wedding on such short notice, that

usually people come already married and honeymoon there. Dennis set up

his camcorder and taped everything. A month or two after we got home, he

sent us a copy which gave us a chance to relive the memory once again.

Thank you, Dennis and Irene, for choosing the Riverside Lodge that week,

and for including us in your joy.

love, fortitude,

strength, backbone, and resolve, who created a loving home for

this biracial group of young people, who themselves have learned (or are

in the process of learning) self-respect, patience, kindness, courtesy,

caring, and the love of living from Muff. We cannot imagine a nicer group

of people with whom to travel. They turned an adventure trip into travel

with friends. Whatever Muff has--and if she were interested--she could

sell it by the bottle and put all the licensed child psychologists out

of business. She has found the secret of making a family out of a group,

and nurturing individuals who like themselves and, therefore, can care

for others. Thank you, Muff, Clara, Boo, J'Mari, Imani, Gita, Chris, Chen,

Emma, Maia (who was to graduate from high school the next month with honors!),

Josh, and Makana. We'll not forget each of you and all you taught us about

what a family can be. And we're still waiting to hear about your trip last

year (1999) to the Amazon!!

love, fortitude,

strength, backbone, and resolve, who created a loving home for

this biracial group of young people, who themselves have learned (or are

in the process of learning) self-respect, patience, kindness, courtesy,

caring, and the love of living from Muff. We cannot imagine a nicer group

of people with whom to travel. They turned an adventure trip into travel

with friends. Whatever Muff has--and if she were interested--she could

sell it by the bottle and put all the licensed child psychologists out

of business. She has found the secret of making a family out of a group,

and nurturing individuals who like themselves and, therefore, can care

for others. Thank you, Muff, Clara, Boo, J'Mari, Imani, Gita, Chris, Chen,

Emma, Maia (who was to graduate from high school the next month with honors!),

Josh, and Makana. We'll not forget each of you and all you taught us about

what a family can be. And we're still waiting to hear about your trip last

year (1999) to the Amazon!!