September 25—October 12, 2005

I. THE BIG PICTURE

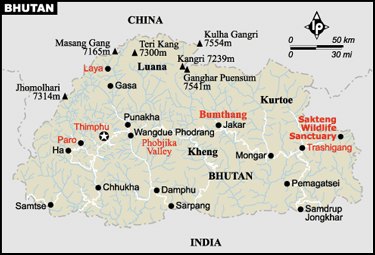

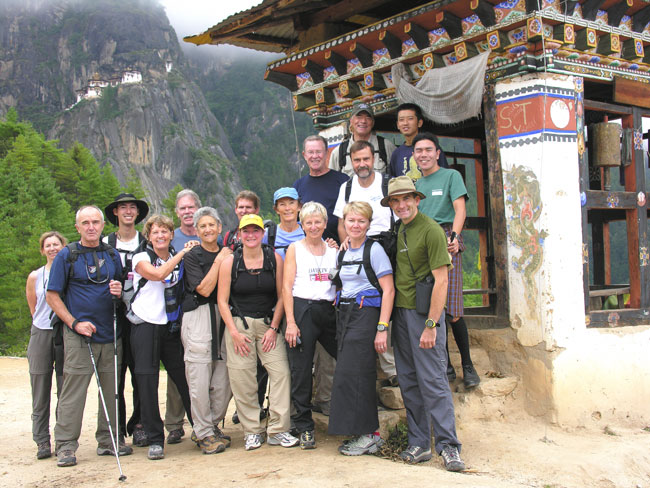

After a year of planning, reading, checking gear, and several meetings, we joined 14 other Boulder County travelers on a 13-day visit the remote Buddhist kingdom of Bhutan. Our trip through 12 time zones took us to LA, Hong Kong, Bangkok, and Calcutta before landing in Paro, Bhutan. We visited the fabled Taktshang (Tiger’s Nest) and the Paro Valley, trekked the popular Jhomolhari Route for eight days, and visited the capital city of Thimphu and the former capital of Punakha. On the return portion of the trip, we took a side trip to Siem Reap, Cambodia, to explore the temple complex at Angkor.

II. HISTORICAL NOTES

The kingdom of Bhutan is impossible to quickly and to

completely embrace, especially in a single trip. It is like no other place we have

visited, yet there were times we felt the comfort of things familiar. The culture

and countryside are replete with contrasts rooted in its centuries of isolation

that are contradicted by signs of recent modern worldliness. Bhutan’s determination

to maintain its cultural heritage and pristine environment may be at risk

by welcoming the outside world to visit, though with restrictions. The

towns and countryside abound in images and relics of the past that remind

residents and travelers alike that this is no ordinary place. Centuries-old

chortens in remote valleys contrast with solar collectors that perhaps

light the traditional houses of yak herders living miles from any road. English

is taught from the earliest grades along with Dzongka, the official language.

There is too much for the western visitor to absorb in one visit, yet the

experience is enriching and enchanting. Bhutan is a special place that

can neither be summed up in a few words or pictures, nor can it ever be

lost and forgotten among a traveler’s list of “interesting” places.

[Note: The size of Bhutan is clear and straightforward: 18,147 square miles is about the size of Vermont and New Hampshire together. Estimates of Bhutan’s population, however, range from 734,340 to over 2,000,000. I can find no explanation for such a disparity. The percent of people living in rural, non-village settings is at least 60% and may be as high as 85%. In short, all demographic figures are estimates and those presented here are based upon the latest Bhutan data.]Buddhism Arrives. Bhutan, (or Druk Yul, “land of the thunder dragon,”) had long

been—intentionally—a country not well known beyond its borders. Even

today, “Where’s that?” is a frequent question about our latest destination.

Until recently, life there has been ruled by religion, laws, and customs rooted in the 8th

century, when Guru Rinpoche arrived from Tibet on the back of a flying tigress

and introduced Nyingma Buddhism to Bhutan. Stories and images of this revered

historical figure are found throughout the country and his importance is

second only to Sakyamuni or Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha.

been—intentionally—a country not well known beyond its borders. Even

today, “Where’s that?” is a frequent question about our latest destination.

Until recently, life there has been ruled by religion, laws, and customs rooted in the 8th

century, when Guru Rinpoche arrived from Tibet on the back of a flying tigress

and introduced Nyingma Buddhism to Bhutan. Stories and images of this revered

historical figure are found throughout the country and his importance is

second only to Sakyamuni or Siddhartha Gautama, the historical Buddha.

Bhutan Unites. In

the 17th century independent and often feuding territorial chiefdoms united

following the arrival from Tibet of Ngawang Namgyal, who traveled throughout

Bhutan teaching and developing a strong political following. In the process

he initiated a system of dzongs, distinctive structures that are a

combination religious and civil fortress built at strategic defensive locations.

(Below is the Paro Dzong and watchtower above it.) He formed political alliances

with neighboring Nepal, Ladakh, and Cooch Behar who together were successful in

defending against the invasions from Tibet. He became the religious ruler of

Bhutan and took the title of the Shabdrung (literally “at whose feet

one submits”). He is credited with unifying Bhutan and establishing

Drukpa Kagyu as the state religion, which continues to this day.

[Note: There are are at least two major schools of Buddhism and several variations of each. Buddhism is not a religion since it does not involve worshipping one god or several gods. It is, rather, a moral and ethical system and philosophy as taught and practiced by revered historical teachers beginning with Siddhartha Gautma in 500 B.C.E. Drukpa Kagyu is a school of tantric Mahayana Buddhism, similar to the Buddhism practiced in Tibet, but different is specific ways. We found a copy of Teachings of Bhudda in every hotel room where we stayed in Bhutan.]

A Kingdom is Formed. Wedged in the foothills

of the Himalayas, pinched between the twin giants of India and Tibet (China), Bhutan for

three centuries existed quietly as a remote Buddhist state comfortable

in its isolation from outside influences. However, by the 19th century

Britain’s political and military influence in the region increased and

Bhutan’s sovereignty was in danger from the threat of invasion from Tibet

well as from British India. In 1907, the country united under one secular

ruler when Ugyen Wangchuck was elected hereditary king of all Bhutan.

He chose to ally Bhutan with the British against Tibet and was able to

maintain the country’s independence. When India gained independence from

Britain in 1947, Bhutan signed a similar treaty with the new Indian government

that assured Bhutan’s sovereignty.

A Kingdom is Formed. Wedged in the foothills

of the Himalayas, pinched between the twin giants of India and Tibet (China), Bhutan for

three centuries existed quietly as a remote Buddhist state comfortable

in its isolation from outside influences. However, by the 19th century

Britain’s political and military influence in the region increased and

Bhutan’s sovereignty was in danger from the threat of invasion from Tibet

well as from British India. In 1907, the country united under one secular

ruler when Ugyen Wangchuck was elected hereditary king of all Bhutan.

He chose to ally Bhutan with the British against Tibet and was able to

maintain the country’s independence. When India gained independence from

Britain in 1947, Bhutan signed a similar treaty with the new Indian government

that assured Bhutan’s sovereignty.

Modern Bhutan. Prior to the 1960s, the country had no system of public education, no health system, no system of currency, and no paved roads or airports. The third king, western educated Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, began a program of modernization that continues to this day. The king signed regional treaties that provided limited immigration and joint economic ventures. Bhutan joined the International Postal Union, sent ambassadors to various countries, and finally became a member of the United Nations in 1971. Western media were permitted to enter the country for the first time in 1974 for the coronation of the present (fourth) king, Jigme Singye Wangchuck. The new hotels built to accommodate the invited guests from outside Bhutan were the beginnings of tourism which has grown slowly and carefully since. Television and the internet were introduced in 1999, though both are rarely found outside the larger cities and towns. An income tax on incomes over 100,000 ngultrums (affecting only the very wealthy) was instituted just four years ago.

Maintaining its traditional ways of life and striving to increase its “Gross National Happiness,” Bhutan welcomes visitors as a valued source of income. The minimum daily charge of $200 per person assures travelers a guide, meals, travel within the country, and a comfortable place to stay (luxury hotels require an additional surcharge, and the daily fee per person can be more during festivals in the fall and spring). In the case of treks, support staff, equipment, and horses or yaks are provided. This hefty fee, which is paid to a licensed Bhutanese travel company who, in turn, pays a percentage directly to the government, helps to maintain the quality of the environment and provide necessary income to meet the needs of a growing population as well as more visitors each year.

[Note: As of November 1, 2005, online sources indicate that the minimal fee remains $200 per day per person, though there are reports this fee has been increased. If you are planning a trip, contact any of the government licensed travel companies for the basic costs.]

III. THE PARO VALLEY

Our arrival in Bhutan was

impressive. There’s no other word for it.  The

last leg of our trip from Calcutta took us directly toward the Himalayas

and on this particular day we could see above the clouds the tops of Annapurna

to the west, Everest in the center, and Jhomolhari to the east. The vista

deserved a camcorder to adequately capture the expanse of snow capped peaks

few in the world have a chance to see.

The

last leg of our trip from Calcutta took us directly toward the Himalayas

and on this particular day we could see above the clouds the tops of Annapurna

to the west, Everest in the center, and Jhomolhari to the east. The vista

deserved a camcorder to adequately capture the expanse of snow capped peaks

few in the world have a chance to see.

As the Druk Air A310 dropped down into the only airport in Bhutan—built on the only space flat enough and long enough (and just wide enough) for a commercial passenger jet to land or take off—we held our breath: the pilot deftly curved through canyons whose walls we felt we could almost touch and found the seam in the valley for the landing. The entire plane applauded when the plane touched down. We meant it.

The airport was our first sign that we had landed someplace quite different from any other airport. The traditional design is a thing of beauty, as well as functionality.

The town of Paro (pop. 20,000)

sits astride the Paro Chhu (River) with a five-block main business

district sandwiched between the river and acres of rice fields. Across

the river is the Paro Dzong, built in the 17th century and restored in

1907 following a damaging fire. Above the dzong is the National Museum,

the former watchtower for the dzong where monk armies could watch the valley

for invaders from the north. A traditional wooden covered bridge connects

the town and the dzong. Our tour of both buildings was our introduction

to Bhutan’s religious heritage. Walking down to town and eventually to

our hotel on the hill opposite the dzong was our first contact with daily

life in a “large” and important Bhutanese town. Folks who live there seem

quite accustomed to western visitors and showed little sign of curiosity

about us. Store and shop clerks were helpful and courteous; they attempted

to speak English or found someone who could.

[Note: Stamp collectors will be dazzled by the display of Bhutanese stamps in the National Museum. For this group, the tour of the museum is a must in order to see the array of remarkably beautiful and special stamps, including those made from holographic images, records and CDs. I would recommend a headlamp or flashlight for a really clear view of the stamps that are displayed in an otherwise dimly lit room.]

The Dechen

Hill Resort in Paro was comfortable,  served

an outstanding buffet of Bhutanese and Indian foods, and we had an excellent

view of the valley in both directions. We had all the hot water we needed,

the beds were clean and comfortable, and the TV offered a dozen stations

in Druk, Chinese, Urdu, Korean, Spanish, and English. What more could we ask for?

served

an outstanding buffet of Bhutanese and Indian foods, and we had an excellent

view of the valley in both directions. We had all the hot water we needed,

the beds were clean and comfortable, and the TV offered a dozen stations

in Druk, Chinese, Urdu, Korean, Spanish, and English. What more could we ask for?

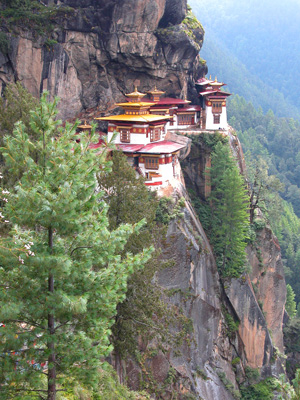

Because Paro’s elevation is about 7,300', guides typically plan a short hike to acclimatize travelers to hiking at elevation. After an eight mile bus ride up the Paro Valley, we climbed a fairly strenuous trail for about three miles to the most famous and most holy monastery in the Himalayan region: Taktshang, the fabled Tiger’s Nest.

Tradition says that Guru Rinpoche arrived at a cave on this site nearly 3,000' above the valley floor. He flew on the back of a tigress and meditated in that cave for three months. It has been a pilgrimage destination ever since and for centuries many holy men have come there to meditate. A monastery was built on the precarious cliff in the 14th century and added to over the years. In 1998, the complex burned and restoration began immediately using photographs and drawings to replicate the structures and the art work it as it was. We were fortunate to not only see it completed but received “special permission” to enter the shrine to Guru Rinpoche within the complex.

On the return trip to Paro, we stopped briefly at one of the two oldest temples in Bhutan, Kyichu Lhakang, built in 659. The temple houses a huge statue of Guru Rinpoche and statues of other revered Buddhist masters. A large gathering of pilgrims sat in the shade of a courtyard listening to a broadcast of a prayer ceremony that was taking place inside. We were invited to enter briefly to witness the ceremony’s chanting accompanied by drums and horns. In a separate room, we saw young monks sitting on the floor having a snack break from their studies and acting like most kids do when the teacher has left the room.

After a short stop in town for some shopping, we returned to the hotel for showers, drinks on the front patio, dinner in town, and final packing for our first day of trekking in the morning.

IV. THE JHOMOLHARI TREK

There are at least a dozen established treks in Bhutan that range in length from three days to three weeks, from easy to challenging. The Jhomolhari Trek is the most popular probably because of its easy access from Paro, and because it offers spectacular views of Bhutan’s sacred mountain, Jhomolhari, home of the goddess Jomo.

[Note: Jhomolhari (also spelled Chomolhari and Jomolhari) was first climbed in 1937 but the expedition claimed they did not set foot on the summit. Another expedition climbed it in 1970 and may have set foot on the summit. However, the sacred peak is now protected and climbing is prohibited. Gangkhar Puensum in north central Bhutan at 7541 meters (24,734') has the distinction of being the world’s highest unclimbed peak and will remain so until the Bhutanese government lifts its ban on mountaineering.]

Day 1. Our trek began at the end of the paved road

north of Paro at the village of Drukgyel Dzong, site of a dzong built in 1647,

but which has deteriorated through disuse and neglect. Our personal gear,

tents, food, cooking fuel, and everything else needed for the trek was

transferred from the bus to the 40 horses that would accompany us the entire

route. We met the nine staff who would cook, clean, set up and take down

our tents, prepare the kitchen, and serve meals. We were also greeted by

scores of children who seemed to love the excitement of the start of the

trek—and the balloons they were offered.

Day 1. Our trek began at the end of the paved road

north of Paro at the village of Drukgyel Dzong, site of a dzong built in 1647,

but which has deteriorated through disuse and neglect. Our personal gear,

tents, food, cooking fuel, and everything else needed for the trek was

transferred from the bus to the 40 horses that would accompany us the entire

route. We met the nine staff who would cook, clean, set up and take down

our tents, prepare the kitchen, and serve meals. We were also greeted by

scores of children who seemed to love the excitement of the start of the

trek—and the balloons they were offered.

[Note: Unlike many third world countries we have visited, there was no begging by kids or adults at any time anywhere during our visit. The children in this end-of-the-road village happily yet timidly received the gift of a balloon offered them with their parents’ approval, but no child asked for one. This was true with the young children all along the trail until the balloons ran out. A Nepali friend here in Colorado had suggested taking balloons to give to children instead of candy or gum. He was right: the balloons were a hit with young kids and we will carry them with us on every trip from now on.]

We stopped a few miles up the wide stony road at the village of Misizam (also spelled Mitshi Zampa) where there was an elementary school with about 20 children in each of three classes. Because one of our guides, Ratu, knew one of the teachers we received an invitation to visit some of the younger classes. One group was in the middle of their English lesson, reading from about a second grade primer. The children were most polite and shyly interested in reading to us.

Beyond Misizam we reached the army post at Gunitsawa where the guides had to show our trek permit. Across the river (the Paro Chhu) was another school complex and living quarters for army personnel. The checkpoint is also the site of a well known and, probably, often photographed water pipe that is shaped like a phallus with two large stones of the same color placed beneath the pipe that shoots out a 5-foot stream of water.

Note: Images of phalluses are found throughout Bhutan in honor of Lama Drukpa Kunley (1455–1529), known fondly as “The Divine Madman.” He traveled throughout Bhutan spreading his style of Buddhism and, apparently, his seed wherever he went. Bhutanese seemed to have embraced his outrageous behavior and have paid him tribute in paintings on buildings, rock sculptures, wood carvings, and water pipes. The symbols have come to mean not only fertility but good luck, prosperity, and they are believed to ward off evil. At Chimi Lhakhang, his temple in Punakha, for a small fee one can receive a fertility blessing—a tap on the top of the head by a 500-year-old wooden phallus carved by Drukpa Kunley himself. Childless couples come from around the world for such a blessing, some successfully. At our age, we took our chances.]

After more than ten miles of hiking we camped at Sharna Zampa (a.k.a. Shana) along the banks of the Paro Chhu which we would follow for the next several days. By later afternoon, the sun was eclipsed by clouds that settled lower and lower, obscuring the mountains on either side of us and putting a chill on our hopes of great views of the Himalayas and Jhomolhari.

Day 2. The track turned to mud and rocks today, the clouds persisted, and the trail was long: 12 or 13 miles by day’s end. We ate a quiet midday meal and continued on through dense forests of blue pine and fir and various deciduous trees. We were quiet as we watched our footing; the woods were quiet as well, making the sound of the rushing river seem all the louder. We rested in camp that evening in hopes that at sunrise we might have our first view of Jhomolhari.

Day 3. At dawn,

the sun broke on the snowcapped peak of Jhomolhari, long enough for us

to take scores of pictures with very dark foregrounds. The scene lasted

less than an hour before gray dense clouds settled over nearly the entire

landscape, especially to our backs as we headed further north toward Jangothang,

our destination for the third camp about 12 miles ahead. Along the way

we passed our first yaks and yak herders: the first family living under

a blue plastic tarp that provided temporary, though smoky shelter, and

the second in a house with a solar panel that would light a single bulb

illuminating the single room. We visited both families, offering a gift

of money for our intrusion and declining an offer of butter tea.

Further along we walked by the half dozen houses that defined the village of Dangochang where the government had built an outreach clinic and housing for visiting medical personnel. It looked as though it had not been used for years. Like government housing in so many places, the buildings have not survived nearly as well as those built hundreds of years ago by people living in them. Another hour up the valley we reached the Jangothang Tourist Base Camp where we would spend two nights.

Day 4. Our camp at Jangothang (13,600') is located at a wide place in the river valley where the views were reportedly outstanding. From here we could hike west to the base of Jhomolhari in a few short hours. To the southeast are lakes for fishing, and to the north the trail continues to the home of a singer-songwriter featured in Michael Palin’s TV series on the Himalayas. Some of us spent the following day at the Jangothang “Base Camp” hiking in the direction of Jhomolhari without seeing the mountain; some went fishing with some success; some scrambled along yak trails on the side of the mountains; and some rested in camp reading and washing clothes. No one went to visit the singer.

In fair weather, I have no

doubt we would have been overwhelmed by the views of the Himalayan crest,

as well as by the surrounding mountains. However, for most of the day we

experienced heavy mist and rain. Judy and I hiked with three others toward

the base of Jhomolhari, hoping the clouds might lift enough to catch a

glimpse of the peak. We followed a river formed by glacial melt for several

miles and then above the river valley on yak trails, avoiding those that

we saw. Yaks are huge, swift for their size, and unpredictable, at least

to us. We gave a wide berth to two males who were engaged in a scuffle.

While we enjoyed the leisurely pace of our hike, the clouds persisted.

While stopped at one point, we heard and saw a massive

ice fall from the glacier on the side of the peak. We returned to a bowl

of hot soup and an afternoon’s rest with a good book.

While stopped at one point, we heard and saw a massive

ice fall from the glacier on the side of the peak. We returned to a bowl

of hot soup and an afternoon’s rest with a good book.

Day 5. Because of the poor weather,

especially at our intended camp just four miles away at a pair of alpine lakes

(where a some of our group fished the day before) at a place called Tso Phu (14,366'),

our head guide, Phurba, decided that we should push on beyond Tso Phu to Chorapang,

crossing the pass at Bang Tue La (a.k.a. Bhonte La) at 16,039'. We would

combine the next two days’ trek and take another rest day. We woke to

rain and started early, climbing out of the valley up a steep incline of

scree and fog. Before we reached the lakes, the rain had turned to snow,

convincing most of us that camping there was not a good idea. Again the

clouds and snow prevented us from viewing Jhomolhari and its neighboring

peak Jitchu Drake, equally spectacular as we saw in pictures in the travel

magazines. The pair of lakes were a dim gray below us.

Day 5. Because of the poor weather,

especially at our intended camp just four miles away at a pair of alpine lakes

(where a some of our group fished the day before) at a place called Tso Phu (14,366'),

our head guide, Phurba, decided that we should push on beyond Tso Phu to Chorapang,

crossing the pass at Bang Tue La (a.k.a. Bhonte La) at 16,039'. We would

combine the next two days’ trek and take another rest day. We woke to

rain and started early, climbing out of the valley up a steep incline of

scree and fog. Before we reached the lakes, the rain had turned to snow,

convincing most of us that camping there was not a good idea. Again the

clouds and snow prevented us from viewing Jhomolhari and its neighboring

peak Jitchu Drake, equally spectacular as we saw in pictures in the travel

magazines. The pair of lakes were a dim gray below us.

By the time we reached the top of the pass at Bang Tue La, we stood in 7" of snow to take our pictures quickly and start down the other side. The descent was steep and made more treacherous because of the icy, muddy conditions on the trail. Even a few horses slipped or fell going down. We did see several herds of blue sheep that run wild at these high elevations, probably in lush green meadows a few days before we arrived. For the most part, however, we watched our footing carefully to avoid a serious fall that could have sent one of us several thousand feet into the valley below. Most everyone had at least a minor slip, some more than others.

We reached our camp at Dhumzo mid-afternoon. We had hiked only about ten miles and were glad to have hot coffee, tea, and soup upon arrival (the horses and staff always got there first, set up tents and the kitchen, and got the water boiling). Because we broke camp in the rain that morning, there were plenty of wet sleeping bags and tents to be dried out. Our spirits were low and we did not cherish the idea of staying here the following day.

That evening, the staff broke

out the bottle of Dragon Rum (produced at Bhutan’s Gelephu distillery in

cooperation with the Bhutanese army) which was dark, thick, and very warming.

After dinner, we celebrated the birthday of one of our group: she received

a traditional white scarf (kata) to mark the occasion and a book

of Bhutan stamps to her great delight. To the surprise of all, the

cook served a decorated birthday cake that he had transported

with the rest of the kitchen and food all the way from Paro. We momentarily forgot

the wet conditions of the day and of the days ahead.

cook served a decorated birthday cake that he had transported

with the rest of the kitchen and food all the way from Paro. We momentarily forgot

the wet conditions of the day and of the days ahead.

Day 6. In spite of the rain, the guides built a bonfire today so we could dry our boots, pants, socks, gloves, and anything else that was wet. The staff cut massive quantities of tall grasses to lay down on the floor of the dining tent which had become a “sea of mud.” Nothing like having a carpeted dining tent! Other than guarding against any clothing that might catch fire, we rested and reorganized our gear for tomorrow’s hiking. During the morning, an older woman with two young children came into camp selling jewelry, clothing, and textiles. We thought her very resourceful and she did rather well for her efforts. By late afternoon the rain stopped and stars were visible after dinner. A good omen.

Day 7. A morning discussion led to the decision to

split the group for this day: one group would make the long push to reach the

camp at Sharna Zampa/Shana, a downhill trail of about 18 miles, and the

others would continue with the original route over the pass at Takalung

La (14,400') and another pass at Thangjue La (13,922'). The former route

would be long but not snowy; the higher route would be about three miles

shorter, but more strenuous and snow-covered. We would meet at Sharna Zampa

for dinner.

Day 7. A morning discussion led to the decision to

split the group for this day: one group would make the long push to reach the

camp at Sharna Zampa/Shana, a downhill trail of about 18 miles, and the

others would continue with the original route over the pass at Takalung

La (14,400') and another pass at Thangjue La (13,922'). The former route

would be long but not snowy; the higher route would be about three miles

shorter, but more strenuous and snow-covered. We would meet at Sharna Zampa

for dinner.

Given the weather conditions and the poor chance for good views of the high county, we chose the longer route. While is was true that we were not snowed upon, the trail was a test of patience and endurance. The mud was deep, the rocks slippery, and there seemed no end to them as we left for Sharna Zampa. We hiked west through one river valley until we joined the trail we had come up on day two which had the worst hiking surface on the way up. Now the mud was deeper and the footing more treacherous. Some of the group were heard to grumble quietly from time to time, but we pushed on. As we finally neared the location of our first night’s camp, we found another group had arrived before us. We backtracked a mile or so to a river crossing and followed the trail to the other side of the river to where our group had set up camp earlier in the afternoon. A young woman at a farm near the bridge had seen the rest of our group going toward the new camp and gestured for us to follow her, which we did until we met up with one of our guides who had come out in the fading light of early evening to show us the way. Needless to say, it was not a trip highlight and we ate quickly and fell into our sleeping bags.

[Note: Keeping warm when camping is important and sometimes sleeping in the best sleeping bags can be improved with the help of a hot water bottle. I’ve not seen one since I was a child. However, every evening as we left the dining tent for bed, we were each given an old fashioned rubber hot water bottle fit in a cloth bag. Not one of our group complained about being uncomfortably cold sleeping.]

Day 8. We walked out today. We woke

knowing we were a scant four or so hours from Drukel Dzong where we had set out over

a week ago: past the army post with its phallic water pipe, past the school (which

was having recess as we passed by waving to some familiar faces), past acres of

rice fields and farm houses, meeting as we did other trekking parties coming towards

us in spotless clothes and clean boots enjoying the warm, sunny weather that we were

finally enjoying.

Day 8. We walked out today. We woke

knowing we were a scant four or so hours from Drukel Dzong where we had set out over

a week ago: past the army post with its phallic water pipe, past the school (which

was having recess as we passed by waving to some familiar faces), past acres of

rice fields and farm houses, meeting as we did other trekking parties coming towards

us in spotless clothes and clean boots enjoying the warm, sunny weather that we were

finally enjoying.

When we arrived at Drukel Dzong, we were each greeted with a kata, a white silk scarf to commemorate a successful trek. Everyone—trekkers, guides, kitchen staff, and “pony boys”—ate a hearty lunch which was spread out on a long table—hot foods, sandwiches, and cold beer. We had a formal ceremony for presenting tips to each staff member personally (Phurba and Ratu, our guides, received theirs at the end of the entire trip.)

After lunch we packed our bags and our bodies on the bus for the return trip to Paro. We spent the night at the Bhutan Mandala Resort (the Dehan was having a temporary water problem) overlooking the Paro Valley. It was like coming home. We luxuriated in hot showers, put on clean clothes we’d left behind, sipped gin and tonics, and ate dinner sitting around a dining table discussing what had been a challenging trek and the significance weather plays in determining travel plans. We didn’t know then that the next four day would be gloriously sunny, even hot as we visited Thimphu, Bhutan’s capital and largest city, and the historic former capital of Punakha. If only the weather during the trek……

[Note: Bhutan has one of the lowest crime rates in the world, maybe the lowest. I don’t know how to account for this fact, except that there must be many Bhutanese of high moral character. We had an example of this that evening in Paro. Walking up the steps of the Mandala Hotel, I didn’t realize I had dropped several hundred dollars on the steps. At dinner that evening, Phurba came into the dining room with a wad of US dollars and, with a grin, announced he was a much more wealthy man than he had been earlier that day. He finally said that he’d found a sum of money that he believed belonged to one of us. Had any of us lost any money? After checking my money belt I was surprised and embarrassed to find that all my $100, $50, $20, and $10 bills that I kept in one slot were gone. The amount I thought I’d had lost was close enough to the amount Phurba found and he was happy to return my money. I guess most of the people in Bhutan are like Phurba.]

V. THIMPHU AND PUNAKHA

Until the 1960s, what few roads existed in Bhutan were narrow, twisting dirt tracks for the few private and government vehicles found in the country. Paved “highways” were part of the government’s effort to create a stronger infrastructure that could move people and goods more easily throughout the country. Today, as we discovered, the roads are still narrow and twisting, though some are paved: one lane—usually about 11' wide—with dirt shoulders on either side that permit vehicles to pass each other with extreme care. Our driver for the entire visit was Tshering Phuntsho, whose display of patience, courage, and experience gave us confidence throughout at all times. He ranks with the Druk Air pilots who fly in and our of the Paro Valley each day. We rarely traveled more than 30 kph (less than 20 mph). We’d read of the trans-Bhutan public bus, the “vomit comet,” in Jamie Zeppa’s memoir of life in Bhutan of the 1980s, Beyond the Sky and Earth, and we were about to better understand how that vehicle got its name.

[Note: There are no trains, domestic air service, and no helicopters in Bhutan. Travel in Bhutan is by foot, bicycle, or motorized vehicles, most of which are buses, trucks, and scooters/motorcycles. We met three bicyclists from the USA who had just begun a bicycle trek across Bhutan, and we met a fellow from New Mexico who had in the past operated motorcycle tours through Bhutan and other parts of the Himalayas. Trekking accidents must be dealt with at the scene and more serious situations require victims to be carried to the nearest road, often many miles away.]

We left the flat expanse of the Paro Valley and were driven by comfortable bus to Thimphu (shown on the right). The 33 miles took us the better part of a Saturday morning. There were, we were told, many cars and trucks on the road and the driving was slow. Nearly an hour out of Paro we had to stop at a checkpoint at Chhuzom, but not before passing Tamchog Lhakhang, one of the few private temples built in 1433 by Thangtong Gyalpo, known as the “Iron Bridge Builder” who originated the use of iron chains for building bridges. In the final 20 miles of the trip we zigzagged through densely wooded mountain valleys with steep sides and deep drop-offs on either side, many terraced rice fields, and a few small villages breaking the monotony. As we approached Thimphu we saw a major road construction project that will soon create a four-lane limited access highway leading to Thimphu.

Thimphu. We

checked into the Druk Hotel in the center of this rapidly growing bustling

city of 50,000. It took a while to adjust to traffic, crowds, and

buildings that made Paro look like a small farming village. But we knew it was Saturday,

a market day, and everyone seemed to be in town for one reason or another.

We were driven down the hill behind the hotel to the public playing fields

to watch an archery match. It had begun about eight o’clock that morning

and would not be over until sometime between five and six in the evening.

Archery is the national sport and is very competitive. The small targets

stand about three feet high are placed 460 feet apart—nearly half again

longer than a football field. It is a cause for celebration when an archer

successfully hits the wooden target (we never saw an archer strike an arrow

within the circles). In spite of the relatively slow action, there is a

certain drama to the event that we found difficult to leave. But the Saturday

market beckoned.

buildings that made Paro look like a small farming village. But we knew it was Saturday,

a market day, and everyone seemed to be in town for one reason or another.

We were driven down the hill behind the hotel to the public playing fields

to watch an archery match. It had begun about eight o’clock that morning

and would not be over until sometime between five and six in the evening.

Archery is the national sport and is very competitive. The small targets

stand about three feet high are placed 460 feet apart—nearly half again

longer than a football field. It is a cause for celebration when an archer

successfully hits the wooden target (we never saw an archer strike an arrow

within the circles). In spite of the relatively slow action, there is a

certain drama to the event that we found difficult to leave. But the Saturday

market beckoned.

It was a short drive to the

weekend market where all manner of local produce, meats and cheeses, crafts

were for sale—everything from trinkets made in India, betel nuts, dried

fish, musical instruments, jewelry, CDs, and more.  Hard

bargaining is expected which adds to the entertainment and shopping experience.

We really enjoyed the bargains and mixing with the throng who didn’t look

twice at the nosy westerners taking pictures in their midst. Like local

markets everywhere, it’s great fun for visitors and locals alike.

Hard

bargaining is expected which adds to the entertainment and shopping experience.

We really enjoyed the bargains and mixing with the throng who didn’t look

twice at the nosy westerners taking pictures in their midst. Like local

markets everywhere, it’s great fun for visitors and locals alike.

After lunch we toured the

textile museum and walked around the outside of the fenced

Takin

Preserve, a mini-zoo devoted exclusively to this strange cross between

a gnu and a musk deer, or according to legend (again involving Lama Drukpa

Kunley, “the Divine Madman”), a cow and a goat. In any case, biologists

place it in a taxonomic class by itself. Because they live in remote areas

of the country and their numbers are dwindling, and because of their connection

to religious mythology, takins are protected as the national animal and

the only zoo in the world dedicated to a single animal was created.

[Note: Some years ago, the king decided that a mini-zoo was not in harmony with religious and environmental principles and he disbanded the zoo. The takins were released but were so tame (or stupid?) that, like the dogs of Bhutan, they wandered the streets of Thimphu looking for food. The best solution seemed to return them to the fenced area now called a “preserve.”]

Following a leisurely afternoon of wandering and

window shopping along the main streets of Thimphu, we had dinner hosted by the

Yangphel Adventure

Travel Company, the company hired to lead our group, and arranged by their

general manager, Karma Lotey. We dined with eleven Bhutanese whose English was

quite good and who shared

many of the personal interests of our group (e.g., a high school teacher and

several students, head of the archery federation, the general manager of

Kuensel, the national newspaper, an army captain, a member of the Ministry

of Communications, a birding guide, and others).

many of the personal interests of our group (e.g., a high school teacher and

several students, head of the archery federation, the general manager of

Kuensel, the national newspaper, an army captain, a member of the Ministry

of Communications, a birding guide, and others).

We ended our visit to Thimphu the next morning with a special-for-us performance of dances and songs that we would have witnessed had we attended a national festival. The professional performers sang and performed masked dances accompanied on traditional instruments. They provided written interpretation of each of the songs and dances, but it may have been enough to let the sounds and images wash over us without attempting to understand the literal meaning of each.

Before leaving Thimphu, we paid short visits to Jungshi Handmade Paper Factory (interesting handmade textures produced from strips from the bark of the daphne tree), and the Folk Heritage Museum, a project of one of the queens to restore and maintain a replica of a traditional farmhouse as it might have been a century ago. After a late lunch, we boarded the bus for our final destination: Punakha.

Punakha. After an hour of climbing

the twisting “National Highway” east out of Thimphu, we arrived at the

pass at Dochu La (elevation 10,300') for a spectacular view of the Himalayas to the

north and a hillside of chortens honoring those who were recently killed by

insurgents. Hundreds of colorful prayer flags blanket the hillside. After the hour

in the bus, it was a pleasure to walk among the monuments and view the mountains in

the background.

During the two-hour descent into the Punakha Valley we passed through small villages, one of which was the site of a cremation ceremony that day, through forests of rhododendron, hemlock, fir—even a stand of daphne at which we stopped and our guides picked samples of—which gave way to orchards of oranges, bananas, bamboo, and other tropical plants, as well as terraced rice fields and vegetable gardens. Finally we leveled off in the beautiful Punakha Valley which is formed by the confluence of the Mo Chhu (Mother River) and the Pho Chhu (Father River) and dominated by the fabulous Punakha Dzong located where the rivers come together.

The dzong was built in the 17th century by the Shabdrung and was the site of an important battle with invaders from Tibet who were repelled by the army of monks living there, a battle that is reenacted at the annual Junakha Tsechu, or festival. The dzong was the seat of the religious government that ruled Bhutan until the 20th century, and the capital of the secular government until the 1950s. It remains the home of the Je Khenpo, the religious leader of the country. The embalmed body of the Shabdrung is in a temple within the dzong, though only four people—the king, the Je Khenpo, and two custodian monks—are allowed into this area. The original building was damaged many times by fires, by an earthquake in 1897, and floods in the 1900s. Each time it was rebuilt using traditional methods (there is a workshop we did not visit below the dzong where visitors can learn about making traditional crafts).

We visited the main room, the “hundred pillar congregation hall,” with its gold paneled columns, beautifully painted murals and art works on the walls, and large statues of the Buddha, Guru Rinpoche, and Shabdrung. Phurba and Ratu, our guides, offered us many insights into the importance of the Punakha Dzong and its place in Bhutan history. Though the trip to Punakha is long and somewhat “out of the way” (and what isn’t in Bhutan?), seeing this particular dzong was as fascinating as our visit to the Tiger’s Nest in the Paro Valley. Neither should be missed.

We also visited Chimi

Lhankhang, the temple of “The Divine Madman.” The temple is small but has been

visited by many people from around the world seeking a fertility blessing. Perhaps

meeting up with all the phalluses throughout our trip raised our

curiosity. Our visit was short: we received the ritual blessing (without any expectations),

gave a small offering (which is expected when visiting any religious building), and walked

down the hill in full sunshine for the very long ride back to Paro from where we would leave

for home in the morning.

curiosity. Our visit was short: we received the ritual blessing (without any expectations),

gave a small offering (which is expected when visiting any religious building), and walked

down the hill in full sunshine for the very long ride back to Paro from where we would leave

for home in the morning.

A FINAL THOUGHT

Our departure from Paro in the morning was early as the misty clouds gave way to sunshine on the back mountains. We again saw Jhomolhari, Everest, and Annapurna from our widow seat as the plane rose above the clouds. It reminded me that for the past two weeks we always had been in the presence of high mountains, though we could not always see them. But that was true of much of trip: There was much we did not see nor could not see while we were in Bhutan, sometimes because of the weather, sometimes because of time limits, and sometimes perhaps because we did not know how to look at what was around us. Michael Palin’s visit taught him this:

“The cultural confusion of East and West, of temples and shopping malls, robes and baseball hats… doesn’t seem to have done much damage to a country where the official language is Dzongkha, official currency in the ngultrum, and the official policy is Gross National Happiness before Gross National Product. Of course, there are telephones and cars and satellite dishes and laptop computers, but they are inside traditional buildings and used by people wearing traditional dress. Bhutan sees no contradiction between its past and its present. Its history is not to be found on display in tourist-friendly heritage parks, but on the street and in the countryside, as part of everyday life.”

If nothing else, I may

have learned better to appreciate the importance—and challenge—of being

a visitor to a new country, not just a traveler. The contrast of cultures,

the differences between East and West, were always apparent. Yet this visitor

from the West was made to feel at home in a new and sometimes bewildering

country quite different than ours. Thank you, Phurba and Ratu (formally

attired in their ghos and their white kabneys draped over their

left shoulders in photo on left), for your insights, your friendship, and your

good humor. You represented your people well and your country with pride. You

and your friends made all the difference between just “traveling through”

and beginning to know and understand the diversity and richness of your country.

The impressions and images will last a lifetime.

|

|

|